Mindwars: Are System-Trusting Beliefs Harmless?

A prospiracy-mentality mirror of conspiracy research.

Abstract

Psychological research on conspiracy theories typically treats “conspiracy mentality” as a unidimensional trait: a stable tendency to suspect that powerful actors secretly collude against the public. High scores on generic measures such as the Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire (CMQ) are associated with lower political trust and participation, reduced vaccine and climate engagement, non-normative behaviour, and prejudice. (Bruder et al., 2013; Douglas, 2021; Jolley et al., 2020). On this basis, the high end of the distribution is widely framed as a social and psychological problem.

This article does not endorse the CMQ as a valid construct. Instead, it uses it as a thought-experiment device. It asks: if one takes such a scale seriously as a trait measure, what follows if the focus is placed on the opposite tail of the distribution? Prospiracy mentality is defined as the conceptual and psychometric inverse of conspiracy mentality: a strong, generalised reluctance to believe that governments, agencies, or elites might engage in harmful, hidden coordination. Prospiracy mentality corresponds to very low CMQ scores, or to agreement with explicit inverse items (“politicians are usually transparent,” “government agencies do not closely monitor ordinary citizens,” etc.) (Bruder et al., 2013).

Using the same style of consequences mapping that has been applied to conspiracy mentality, it sketches how extreme system-trust could plausibly generate its own pattern of social harms: uncritical support for rights-eroding policies, tolerance of institutional misconduct, under-reaction to real conspiracies, and endorsement of information-control regimes that suppress legitimate dissent (Douglas, 2021; Howard, 2025a, 2025b, 2025c; Lewandowsky et al., 2022). Fully inverted causal diagrams are introduced in which exposure to elite narratives and prospiracy beliefs mediate “deleterious compliance” rather than “deleterious deviance.”

The aim is not to replace one pathology with another, but to show that once a one-dimensional “conspiracy mentality” trait is reified, both tails can be problematised with equal ease. The fact that only the suspicious tail has been targeted in practice reveals an underlying assumption: that institutions and elites are sufficiently benign that doubt about them is dangerous, while uncritical trust is harmless (Howard, 2025b, 2025c). A more adequate framework would abandon tail-hunting and focus instead on calibrated suspicion—how citizens tune their trust in power to history, incentives, and evidence.

1. Introduction

Over the last decade, psychological research on conspiracy theories has converged on a familiar template. People are located along a “conspiracy mentality” continuum using generic scales; those with higher scores are shown to have lower trust in institutions, lower participation in conventional politics, weaker support for vaccination and climate policies, greater endorsement of non-normative or illegal action, and more prejudice toward outgroups (Douglas, 2021; Jolley et al., 2020). From these patterns, a broad conclusion is drawn: conspiracy beliefs are not harmless and high conspiracy mentality constitutes a risk factor for individuals and societies.

This literature relies heavily on tools such as the Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire (CMQ) and the Generic Conspiracist Beliefs scale, which ask respondents to rate the likelihood that governments, politicians, agencies, and secret organisations operate covertly, deceive the public, and exert hidden influence (Brotherton et al., 2013; Bruder et al., 2013). The resulting scores are treated as trait-like indicators of a general conspiratorial mindset.

Two interpretive moves are then made. First, there is trait reification: suspicion toward powerful actors is treated as a stable, person-level disposition rather than a context-sensitive judgement (Brotherton et al., 2013; Bruder et al., 2013). Second, there is one-sided pathologisation: elevated scores are repeatedly tied to negative outcomes; low scores are implicitly coded as psychologically healthy and civically desirable (Douglas, 2021; Jolley et al., 2020).

Critical work has argued that this architecture embeds an asymmetry: scepticism is treated as the pathology, while the institutions being doubted are left methodologically off-stage (Howard, 2025b, 2025c). In Lewandowsky et al.’s (2022) review of misinformation and scientific credibility, for example, the primary concern is how to restore trust in science, not how to empirically scrutinise scientific institutions as potential sources of error, bias, or capture.

This article does not attempt to validate the CMQ. In fact, much of the critical work it is built on questions whether it makes sense to collapse heterogeneous beliefs—about different institutions, in different times and places—into a single number (Howard, 2025c). Instead, this paper accepts the scale as a hypothetical premise and explore where that leads. It asks:

If conspiracy mentality is a meaningful trait, why has only one tail of the distribution been problematised?

To answer, the idea of prospiracy mentality—the conceptual mirror image of conspiracy mentality—is introduced and a “total inversion” strategy is employed which inverts:

- The trait (from suspicion to hyper-trust)

- The scale (from high CMQ to low CMQ / high prospiracy)

- The standard causal model (from “misinformation → conspiracy → deviance” to “authorised narratives → prospiracy → harmful compliance”) (cf. Lewandowsky et al., 2022).

The exercise functions as a reductio: by showing how easily the measurement regime can be flipped to target the opposite tail, it exposes how much depends, not on the statistics, but on unspoken assumptions about the innocence of institutions and the danger of doubting them (Howard, 2025b, 2025c).

2. The CMQ as a Hypothetical Trait Instrument

The English CMQ consists of five items, each rated on a 0–100 likelihood scale. Respondents indicate how likely they think it is that, for example, many very important things happen that the public never hears about, politicians usually do not tell the true motives for their decisions, government agencies closely monitor all citizens, apparently unconnected events result from secret activities, and secret organisations greatly influence political decisions (Bruder et al., 2013). High CMQ scorers endorse these statements as likely or certain; low scorers treat them as unlikely or certainly not the case.

The CMQ questions are:

I think that…

1 … many very important things happen in the world, which the public is never informed about.

2 … politicians usually do not tell us the true motives for their decisions.

3 … government agencies closely monitor all citizens.

4 … events which superficially seem to lack a connection are often the result of secret activities.

5 … there are secret organizations that greatly influence political decisions.

There are at least three conceptual problems with taking this at face value as a “mentality” trait: the items mix domains and actors with very different histories and incentive structures; the truth value of the statements varies by country, time period, and sector; and both justified and unjustified suspicion are collapsed into one index (Brotherton et al., 2013; Howard, 2025c).

These problems are bracketed. The remainder of this paper says:

Suppose the CMQ is exactly what its authors intend: a reasonably valid, unidimensional measure of “conspiracy mentality” as a generalized expectation of covert, malevolent coordination by powerful actors (Bruder et al., 2013).

On that assumption, high values correspond to a chronic tendency to suspect secrecy and malice; low values correspond to chronic reluctance to do so. Under this premise, it becomes legitimate to analyse either tail as a potential risk profile.

The existing literature has already executed that logic on the high tail, linking elevated scores to lower trust and compliance in domains such as politics, climate, and public health (Douglas, 2021; Jolley et al., 2020). We will now run it, deliberately and systematically, on the low tail.

3. From Conspiracy Mentality to Prospiracy Mentality

This paper defines prospiracy mentality as the conceptual and psychometric inverse of conspiracy mentality.

Where conspiracy mentality treats hidden coordination by powerful actors as common and malign, prospiracy mentality treats it as rare, negligible, or essentially benign. It is not mere absence of suspicion; it is a positive stance that important events are generally transparent to the public, that politicians are usually candid about their motives, that government surveillance is limited and reasonable, that apparent coincidences are rarely driven by secret plotting, and that political decisions are mostly shaped by visible, accountable actors rather than secret organisations (Bruder et al., 2013).

Psychometrically, prospiracy mentality can be modelled in two equivalent ways. One is reverse-scoring the CMQ: high prospiracy corresponds to consistently low CMQ responses (e.g., 0–20% likelihood on all items). Another is constructing explicit inverse items, such as “Most very important things that happen in the world are openly communicated to the public” or “Government agencies do not closely monitor ordinary citizens.” In practice, these are two descriptions of the same position.

A person with high prospiracy mentality, in this sense, does not just lack conspiratorial thinking; they affirm, with confidence, that power is structurally safe and mostly honest. Under the thought-experiment assumption that the CMQ validly captures a real trait, it is coherent to talk about a conspiracy tail (hyper-suspicion) and a prospiracy tail (hyper-trust), with many people clustering in the middle (Bruder et al., 2013). The question is whether both tails should be of interest to researchers concerned with social harm, or only one (Howard, 2025b).

4. Fully Inverted Causal Models

A common schematic in the literature depicts a pathway where exposure to misinformation or conspiracy content (often via social media) increases conspiracy beliefs, which then produce “non-normative, deleterious behaviour” such as vaccine refusal, vandalism, or support for political violence (Douglas, 2021; Jolley et al., 2020; Lewandowsky et al., 2022). A more nuanced version adds psychological and social motivations that drive exposure, belief, and behaviour jointly.

To perform a full inversion, the formal structure is retained and the content flipped.

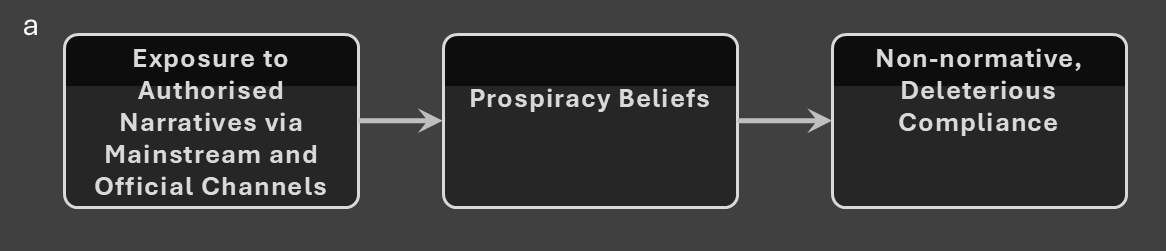

4.1 Simple chain: From authorised narratives to deleterious compliance

In the prospiracy model (Figure: a), the chain reads:

- Exposure to authorised narratives via mainstream and official channels (e.g., government press conferences, established media, institutional campaigns)

- Strengthens prospiracy beliefs (high confidence that institutions are transparent, benign, and non-collusive; low CMQ / high prospiracy)

- Which increase non-normative, deleterious compliance (support for and participation in policies that are harmful, rights-eroding, or captured, precisely because they are promoted by trusted institutions).

Where the original model worries abot people defecting from official guidance under the influence of misinformation (Douglas, 2021; Lewandowsky et al., 2022), the inverted model worries about people following official guidance too far, even when that guidance is self-serving or mistaken (Howard, 2025a).

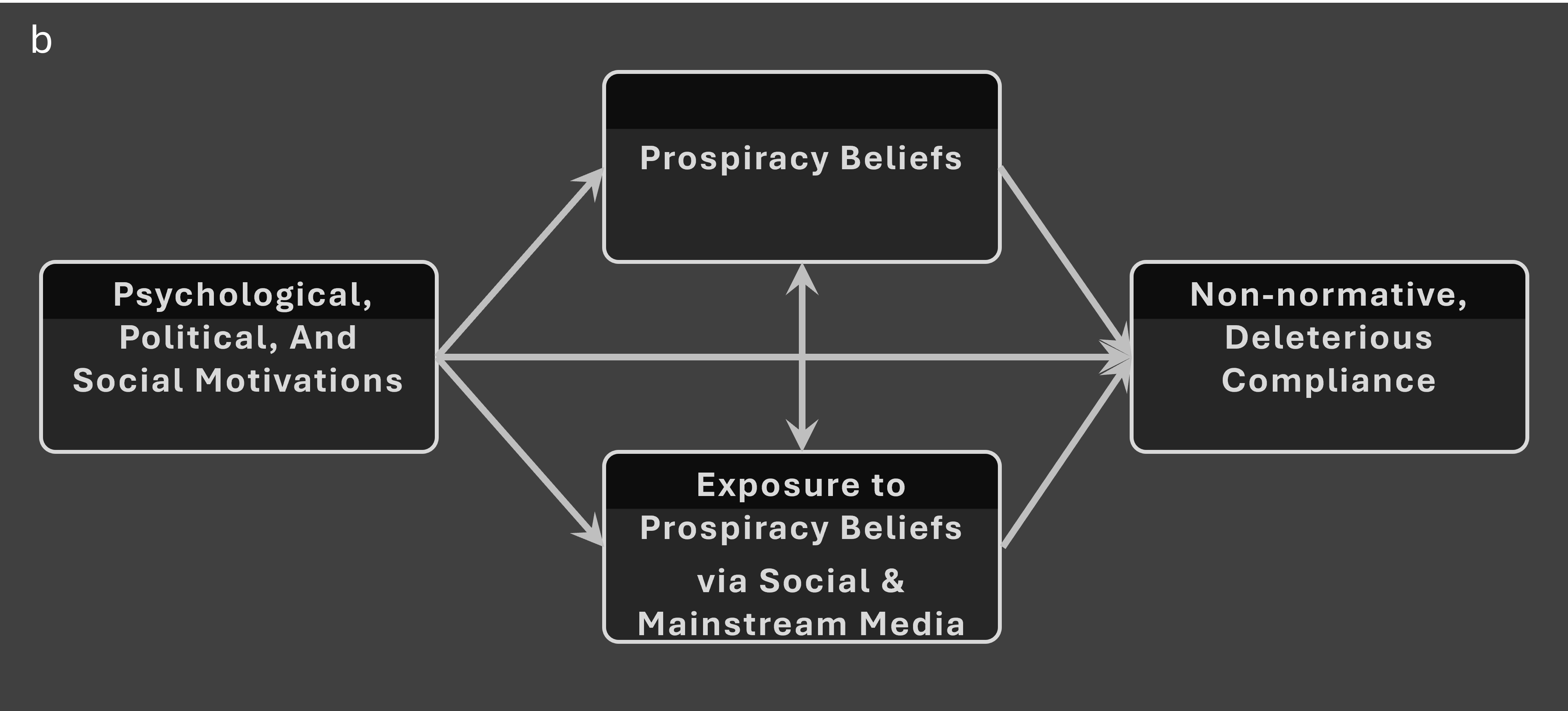

4.2 Richer model: Motivations, prospiracy, and feedback loops

The extended prospiracy model (Figure b) adds psychological, political, and social motivations that feed into both exposure and belief: desire for order and stability, identity as a “reasonable, pro-science, pro-institution” citizen, and social or professional incentives to align with prestigious sources (Douglas, 2021; Howard, 2025b, 2025c).

These motivations increase exposure to authorised narratives (selection of mainstream and official sources, avoidance of outlets coded as “conspiratorial” or “fringe”), promote prospiracy mentality (“they” are fundamentally on our side), and directly feed compliance with contentious policies (support for emergency powers, broad mis/disinformation rules, expanded surveillance) (Howard, 2025a; Lewandowsky et al., 2022).

Prospiracy beliefs, in turn, reinforce selective exposure (“trusted sources” are seen as sufficient) and support behaviours that further entrench the authority of the same institutions (voting patterns, endorsement of regulations, social policing of dissent). Over time, this creates a positive feedback loop: compliant behaviours strengthen institutional capacity to shape narratives, which reinforces prospiracy beliefs in already trusting citizens, which increases their support for further expansion of institutional control (Howard, 2025a, 2025b).

Again, this is not presented as a proven causal network. It is a structurally parallel possibility that becomes available the moment one reifies a “mentality” trait and allows that both its extremes might shape behaviour.

5. Plausible Consequences of Prospiracy Mentality

The consequences literature shows that high conspiracy mentality correlates with patterns such as lower institutional trust, reduced participation, vaccine hesitancy, climate scepticism, non-normative action, and prejudice (Douglas, 2021; Jolley et al., 2020). This section outlines the mirror-image consequences that high prospiracy mentality could plausibly have, using the same domains and the same willingness to attribute “harms” based on institutional performance metrics.

5.1 Politics and accountability

Where high conspiracy mentality is linked to political withdrawal and support for non-normative protest (Douglas, 2021), prospiracy mentality is likely to produce:

- Uncritical electoral participation—voting reliably for mainstream parties and incumbents on the assumption that “they are doing their best,” irrespective of corruption records or policy failures.

- Low demand for oversight—weak support for stronger investigative journalism, whistleblower protections, and anti-corruption institutions, because serious malfeasance is assumed unlikely (Howard, 2025b).

- Support for speech restrictions—willingness to back laws and platform policies that target “disinformation,” “extremism,” or “conspiracy theorists,” trusting that such categories will be applied fairly and accurately (Howard, 2025a; Lewandowsky et al., 2022).

At scale, this constellation of attitudes can reduce democratic feedback. Institutions receive continuous legitimation but relatively little pressure to correct self-serving behaviour.

5.2 Science, medicine, and public health

High conspiracy mentality in health contexts predicts lower vaccination intentions and attraction to alternatives; it is therefore framed as a barrier to effective public health (Douglas, 2021). The mirror risk in prospiracy mentality includes:

- Over-deference to official claims—acceptance of rapidly evolving or even contradictory guidance with little scrutiny, under the assumption that authorities are always acting on the best available evidence (Lewandowsky et al., 2022).

- Tolerance of opaque decision-making—weak insistence on transparency regarding data, modelling assumptions, conflicts of interest, or commercial entanglements.

- Endorsement of strong information control—support for content removal, labelling, and punitive measures against dissenting scientists or clinicians, out of a desire to “protect the public” (Howard, 2025a; Lewandowsky et al., 2022).

In complex, politicised health systems, this profile allows errors and conflicts to persist longer and makes it easier for powerful actors to manage controversy through narrative control rather than open argument (Howard, 2025c).

5.3 Climate and environmental policy

Conspiracy mentality has been linked to climate scepticism and reduced willingness to adopt pro-environmental behaviours (Douglas, 2021). By contrast, high prospiracy mentality is likely to manifest as:

- Acceptance of headline narratives with little attention to policy design—endorsing any measure presented as “following the science,” regardless of who benefits or bears the costs (Lewandowsky et al., 2022).

- Dismissal of concerns about lobbying and greenwashing as conspiracist, even when evidence of corporate influence is available (Howard, 2025b).

- Weakness in contesting unjust or ineffective climate strategies, because questioning the governance layer feels like doubting science itself.

Thus, instead of climate inaction, the prospiracy risk is climate policy capture: the public backs climate action in name while missing crucial questions about fairness, feasibility, and vested interests.

5.4 Intergroup relations and civil liberties

Conspiracy mentality about specific groups can fuel prejudice and support for discrimination (Jolley et al., 2020). Prospiracy mentality can fuel prejudice of a different kind:

- Reflexive trust in institutional labelling of “extremists,” “radicals,” or “conspiracy theorists”—taking these categories as accurate without investigating their basis (Howard, 2025b).

- Underestimation of systemic discrimination or targeted abuse—discounting reports from marginalised groups that imply coordinated wrongdoing by respected institutions.

- Support for expansive security measures—backing surveillance or counter-extremism policies that disproportionately affect certain communities, assuming that institutions would not misuse such power (Howard, 2025a).

Here the harm pattern is not outgroup hatred originating “from below,” but the social endorsement of institutional suspicion directed downward.

5.5 Organisations and workplaces

In organisational research, conspiracy beliefs about one’s employer are linked to lower satisfaction and higher turnover intentions (Douglas, 2021). A strong prospiracy mentality inside organisations may have effects such as:

- Compliance with unethical directives—employees assume leadership would not deliberately act against staff or clients, so they go along.

- Delayed recognition of wrongdoing—patterns of fraud, harassment, or safety violations are interpreted as misunderstandings until they become undeniable.

- Informal marginalisation of sceptical colleagues—staff who raise concerns about collusion or cover-up are labelled negative or “conspiracy-minded.”

The net result is that organisations become more hospitable to genuinely conspiratorial conduct at the top while appearing harmonious and loyal for longer.

5.6 Crisis governance and “information emergencies”

In crises (pandemics, terror attacks, financial shocks), conspiracy mentality can produce disobedience and alternative narratives (Douglas, 2021; Lewandowsky et al., 2022). Prospiracy mentality, especially when combined with strong emergency framing, can produce:

- High tolerance for extraordinary measures—acceptance of lockdowns, curfews, or sweeping digital controls with minimal scrutiny of proportionality or exit conditions (Howard, 2025a).

- Support for semi-permanent information regimes—normalisation of mis/disinformation taskforces, “infodemic management,” and close coordination between states, platforms, and expert bodies, predicated on the belief that these actors will self-police (Howard, 2025a; Lewandowsky et al., 2022).

- Stigmatisation of dissent as risk—treating those who question crisis policies as threats rather than as potential correctives (Howard, 2025c).

This may stabilise short-term crisis response but risks entrenching long-term architectures of control.

6. Democratic and Civil-Liberties Harms of Prospiracy Mentality

If prospiracy mentality is taken seriously as “chronic over-trust in powerful actors,” then its most serious consequences are not in consumer choices or health behaviours, but in how it reshapes the political opportunity structure for restricting rights. Democracies do not lose press freedom, privacy, or due process in one dramatic stroke; they lose them incrementally, via laws and policies that are repeatedly justified as necessary responses to exceptional threats (Howard, 2025a, 2025b). At each step, high-prospiracy citizens—those who score very low on items such as “government agencies closely monitor all citizens” or “politicians usually do not tell us the true motives for their decisions”—are the segment most likely to supply assent (Bruder et al., 2013).

A first channel is lowering the cost of war and security overreach. Historical cases such as the Gulf of Tonkin escalation in Vietnam and the 2003 invasion of Iraq illustrate how much depends on whether publics and legislators treat official threat narratives as inherently credible. When large portions of the citizenry operate with a prospiracy prior—assuming that political leaders and intelligence agencies would not misrepresent existential risks—they are more willing to accept casus belli on thin or contested evidence. Dissenting experts, inspectors, or journalists can then be dismissed as naïve or “politicised,” and legislative bodies face less pressure to demand corroboration before authorising force. The downstream harms are familiar: large-scale loss of life, long-term regional instability, and expansions of executive power that are difficult to roll back (Howard, 2025b). In this sense, high prospiracy mentality functions as an electoral and opinion-poll subsidy for policies that curtail both foreign lives and domestic checks on the war-making authority.

A second channel is normalisation of emergency and security legislation. In the wake of terror attacks or other shocks, liberal democracies often enact broad packages of anti-terror or national-security laws: expanding surveillance powers, lowering thresholds for detention or designation, and increasing the use of secret evidence or closed proceedings. Whether these changes remain exceptional or become quasi-permanent depends partly on how quickly and how strongly publics push back. Individuals who cannot readily imagine that authorities might overreach—those who consider widespread monitoring of citizens or misuse of security powers to be “extremely unlikely”—are more inclined to accept official assurances that new tools will be “used only against the worst offenders.” Their prospiracy stance translates into political support for measures that, in practice, can be and have been repurposed against protesters, journalists, and marginalised communities (Howard, 2025a, 2025b).

Third, prospiracy mentality weakens societal alarm systems and social defences. Democracies rely on a distributed network of “early-warning sensors”: investigative reporters, whistleblowers, civil-society organisations, minority parties, and sceptical citizens (Howard, 2025c). When concerns are raised about covert programmes—such as mass surveillance regimes later revealed by whistleblowers—high-prospiracy audiences are structurally inclined to interpret these warnings as exaggerated, unpatriotic, or “conspiratorial.” Their default trust in institutions leads them to side with official denials and to accept secrecy as necessary. This delays recognition of genuine abuses and reduces the reputational cost to governments of operating in legally grey or secretive ways. By the time a scandal becomes undeniable, the relevant architectures (technical systems, international data-sharing agreements, special courts) are often deeply entrenched.

Finally, prospiracy mentality supports expansive information-control regimes by treating them as neutral guardians of democracy rather than as political instruments. As states and platforms increasingly frame “misinformation,” “disinformation,” and “extremism” as existential threats, high-trust citizens are the most receptive to calls for aggressive content moderation, pre-emptive “prebunking,” and coordinated de-amplification of certain narratives (Lewandowsky et al., 2022). Because they assume benign intent on the part of governments, regulators, and expert bodies, they are less likely to insist on strict safeguards, transparency, and appeal mechanisms. They also tend, in everyday interactions, to stigmatise those who question official lines as irresponsible or dangerous (Howard, 2025a, 2025c). This combination—legal and technical tools from above, social shaming from below—can narrow the range of permissible discourse in ways that are difficult to reverse, particularly when alternative viewpoints concern exactly the kinds of institutional failures or collusions that high-prospiracy individuals find hard to contemplate.

Viewed through this lens, citizens at the prospiracy extreme are not simply “good Democrats” or “loyal Republicans” with high institutional trust. They constitute a structural vulnerability for democratic and rights-based orders: a constituency that repeatedly grants benefit of the doubt to power in precisely those moments when doubt is most warranted.

7. What the Prospiracy Inversion Reveals

The prospiracy thought experiment is not offered as an empirical fact; it is offered as a mirror. Once you:

- posit a one-dimensional “conspiracy mentality” trait;

- treat generic items like the CMQ as a valid measure;

- show that high scores correlate with institutionally inconvenient behaviours (Douglas, 2021; Jolley et al., 2020)

you are already in a position where both tails of the distribution can be cast as problematic: high scores as deviant resistance to institutions, and very low scores as deviant over-compliance with institutions.

The inversion makes this symmetry explicit and adds a label—prospiracy mentality—to the neglected tail. The important observation is that, despite this symmetry, the field has largely chosen to pathologise the suspicious tail and leave the trusting tail unexamined or implicitly normative (Howard, 2025b, 2025c). That choice is not forced by the data or the measurement model. It is an ethical-political decision about where “the problem” is located: in citizens’ doubts rather than in power’s behaviour.

Seen this way, the prospiracy paper functions as a reductio of the trait approach. If you are comfortable turning a generic suspicion score into a risk label, you should, by the same logic, be comfortable turning a generic trust score into a risk label. If that second move feels illegitimate or offensive, it suggests that the underlying project is not neutral measurement but one-sided policing of how much doubt about institutions is acceptable (Howard, 2025b; Lewandowsky et al., 2022).

8. Beyond Tail-Hunting: Toward Calibrated Suspicion

The point of this exercise is not to simply flip the stigma. It is not to argue that “prospiracy mentality” should now replace “conspiracy mentality” as the favourite pathology. Treating either tail as the problem leaves the more fundamental issue untouched: the assumption that suspicion of power can be meaningfully captured as a decontextualised personal trait, independent of what power is doing (Howard, 2025c).

A more promising direction would abandon the idea that trust is intrinsically healthy and distrust is intrinsically disordered, and instead ask how people calibrate their suspicion in light of historical evidence of conspiracies, cover-ups, and institutional failure; their own experiences with public and private authorities; and the incentives and constraints operating on different institutions (Howard, 2025b, 2025c).

Such a framework would treat justified and unjustified suspicion as distinct, model how real conspiracies and scandals reshape citizens’ priors, examine how institutional transparency, responsiveness, and accountability affect trust and distrust over time, and evaluate interventions (including “inoculation” or prebunking) not just by whether they increase compliance, but by whether they improve people’s ability to distinguish trustworthy from untrustworthy behaviour (Douglas, 2021; Lewandowsky et al., 2022).

From this perspective, the most socially desirable position is neither maximal suspicion nor maximal trust but calibrated suspicion: a stance that recognises both the genuine need for cooperative institutions and the reality that powerful actors sometimes collude, deceive, or self-protect.

9. Conclusion

This paper has performed a deliberate inversion of the conspiracy-mentality paradigm. By temporarily accepting the CMQ as a valid trait measure and introducing its mirror, prospiracy mentality, it defines system-trusting beliefs as the conceptual counterpart to conspiracist beliefs; built fully inverted causal models in which exposure to authorised narratives and prospiracy beliefs mediate harmful over-compliance; outlined plausible domains in which extreme system-trust can produce its own pattern of deleterious outcomes; and shown that the asymmetry in existing research—one tail medicalised, the other canonised—is not a methodological necessity but a reflection of deeper commitments about the benignity of institutions and the danger of doubting them (Douglas, 2021; Howard, 2025a, 2025b, 2025c; Lewandowsky et al., 2022).

The exercise is, at root, a critique performed from inside the target framework. If it is possible to generate a paper like this largely by inverting signs, reversing scales, and relabelling boxes in existing diagrams, then the original framework is probably too blunt to capture how people actually relate to power. A one-dimensional “conspiracy mentality” score cannot, on its own, tell us when suspicion is justified, when trust is warranted, or how institutional incentives shape both.

The real question is not “How do we eliminate conspiracy mentality?” or “How do we cultivate prospiracy mentality?” It is:

How do we help citizens develop accurate, context-sensitive expectations about institutions—expectations that neither ignore the possibility of conspiracy nor treat it as ubiquitous, and that resist credulous acceptance of both institutional and counter-institutional narratives?

That requires something much closer to disciplined open-mindedness than to simple “trust” or “distrust.” The sceptical lens has to be pointed in both directions: at governments, corporations, and legacy media, and at alternative media, influencers, and oppositional movements. The appropriate stance is not permanent neutrality, but delayed commitment: a willingness to withhold endorsement of any strong narrative—official or dissident—until the evidential and incentive structure is reasonably clear. Sometimes institutional accounts will turn out to be more accurate; sometimes counter-narratives will; sometimes both will be self-serving in different ways, and the correct response is to keep the file open rather than force a verdict.

Answering that challenge means turning the empirical lens not only on publics, but also on the behaviour and communication practices of the institutions whose trustworthiness is so vigorously defended, and on the counter-institutions that contest them (Howard, 2025a, 2025c; Lewandowsky et al., 2022). Only by analysing how all of these actors generate, filter, and weaponise information can we move beyond tail-hunting on a generic “mentality” scale and toward a more realistic account of calibrated suspicion—one in which citizens learn to routinely ask, of any story they are offered: Who benefits if I believe this? What evidence is missing? And what do I gain by waiting before I decide who is right?

References

Brotherton, R., French, C. C., & Pickering, A. D. (2013). Measuring belief in conspiracy theories: The Generic Conspiracist Beliefs Scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 279. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00279

Bruder, M., Haffke, P., Neave, N., Nouripanah, N., & Imhoff, R. (2013). Measuring individual differences in generic beliefs in conspiracy theories across cultures: Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 225. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00225

Douglas, K. M. (2021). Are conspiracy theories harmless? The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 24, e13. https://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2021.10

Howard, S. (2025a, November 24). Mindwars: Managers of mistrust – Why … Substack. Retrieved November 25, 2025, from https://thestyxian.substack.com/p/mindwars-managers-of-mistrust-why

Howard, S. (2025b, October 20). Mindwars: The original sin – How the … Substack. Retrieved November 25, 2025, from https://thestyxian.substack.com/p/mindwars-the-original-sin-how-the

Howard, S. (2025c, November 2). Mindwars: The self-sealing science of conspiracy theory theorists (CTTs). Substack. Retrieved November 25, 2025, from https://thestyxian.substack.com/p/mindwars-the-self-sealing-science

Jolley, D., Meleady, R., & Douglas, K. M. (2020). Exposure to conspiracy theories increases prejudice and discrimination. British Journal of Psychology, 111(1), 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12302

Lewandowsky, S., Cook, J., Schmid, P., Holford, D. L., Finn, A., Leask, J., Thomson, A., Lombardi, D., Al-Rawi, A., Amazeen, M. A., & van der Linden, S. (2022). Strengthening scientific credibility against misinformation and disinformation: Where do we stand now? Drug Discovery Today, 27(6), 1540–1553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2022.03.007

Published via Journeys by the Styx.

Mindwars: Exposing the engineers of thought and consent.

—

Author’s Note

Produced using the Geopolitika analysis system—an integrated framework for structural interrogation, elite systems mapping, and narrative deconstruction.