Mindwars: The Conspiracy Trait Machine – Why Germany Matters

A decade of papers from one conspiracy theory theorist’s circle doesn’t just “explain” why people believe conspiracies—it builds a psychometric machine that traps political suspicion inside personality scores, ready for platforms, policymakers and “resilience” programmes.

Over the last ten years, if you’ve seen a sober explainer asking “Why do people believe conspiracy theories?”, you’ve probably touched the same small research world without realising it. The charts about “conspiracy mentality”, the headlines about “right-wing conspiracists”, the think-tank slides about “psychological vulnerabilities” to disinformation—they tend to trace back to a handful of European labs, and one statistical hub in particular.

But that’s not what this piece is about.

What matters here is not any one paper, or any one media hit, but what happens when you line up a cluster of outputs from the same circle and treat them as a single object. In my Geopolitika CSIS piece on the Maduro raid, I did that with one week of think-tank content and asked: what kind of world gets normalised when you let that machine run on autopilot? Here, we’re going to do the same thing for conspiracy psychology: take a decade of Roland Imhoff–linked work on “conspiracy mentality” and ask what kind of trait machine it has built, and for whom.

If you’ve read the CONSPIRACY_FX piece on Mindwars—“Conspiracy_FX Clusters—Who Runs the Category Factory”—you’ve already seen the wide shot: conspiracism research as an integrated production line where raw distrust goes in one end and “evidence-based” consequences come out the other. You don’t need that whole map again here. What matters for this story is the European calibration unit sitting in the middle of it—and Imhoff’s role inside that unit.

Zoom in on that factory map and Germany shows up as a two-node hub:

- Tübingen/Göttingen (Sassenberg, Pummerer, Winter)—the intervention lab. This is where you get norm-cue experiments, appraisal models, prebunking and “inoculation” field tests: prototypes for changing how people think and talk, later packaged for EU-style “resilience” programmes.

- Cologne/Mainz (Imhoff, Lamberty, Klein on the slide)—the instrument custody and methods spine. This is where the gauges live. Items like “Powerful people pull the strings behind the scenes” are treated as indicators of a general “conspiracy mentality”; measurement invariance tests, multi-wave panel models, RI-CLPM pipelines, ideology and prejudice linkages are the quiet technical work that keeps that dial stable across countries and time, continuously trading concrete political content for statistical cleanliness.

Across both nodes runs the same statistical grammar: fit indices as quality control, invariance regimes as border checks, longitudinal templates as proof that the thing being measured really “exists”. That’s what lets multi-nation claims about “conspiracy mindset”, “right-wing asymmetry” or “plausibility filters” sail through peer review and land in policy briefs without anyone reopening the basic question: should suspicion of power be a trait at all?

This article stays mostly on that second node. Not re-touring the whole factory from CONSPIRACY_FX; but looking at the Cologne/Mainz node to and see what happens when the people in charge of custody of the gauges—Imhoff and his colleagues—spend a decade tightening, polishing and exporting the very instruments that now define what “conspiracy thinking” even is. The rest of the piece walks through that cluster—scale work, profile work, corruption maps, plausibility filters—and asks the only question that matters for a political animal: who does this trait machine serve, and what kind of suspicion does it leave no legal or cognitive space for?

There’s a reason this hub is in Germany. Post-war German political culture runs on a double project: memory and trust-building at home, integration and “stability” in Europe. You get an unusually dense mix of Holocaust education, anti-extremism programmes, political-education foundations, and a research funding system (DFG, BMBF, EU Framework money) that is very comfortable backing work on prejudice, antisemitism, “democratic resilience” and now disinformation. Imhoff’s own grant record sits squarely in that stream: DFG projects on secondary antisemitism, on “taking a measure of comparative thinking”, on German victimhood memories and how they’re transmitted—plus German-Israeli foundation money for work on Holocaust representations and German-Israeli relations. Thematically, the same ecosystem is now spawning programmes like the DFG Priority Programme “Rethinking Disinformation (Re:DIS)”, which pulls philosophers, psychologists and lawyers into a shared frame around epistemic threats and misinformation. You don’t have to turn this into a conspiracy to see the structural fit: if you were designing a place where “suspicion of power” could be converted into a manageable psychological construct—grounded in memory politics at home and sold as “resilience” and “trust” in Brussels—a well-funded German social psychology chair would be very near the top of the list.

In that sense this article sits alongside, not above, the earlier Mindwars pieces. If “The Original Sin — How the CMQ Turned Distrust into a Diagnosis” sketched the birth of conspiracy mentality, and “CTTs, the Operating Class and the Governance of Suspicion” mapped the wider operating system that now runs on top of it, this piece zooms in on one of its key modules: the Imhoff cluster as the Cologne/Mainz mindset factory. This article therefore walks through what that factory has produced—scales, profiles, maps, filters—and asks what kind of world you get when a small European hub ends up in charge of the gauges that now define “conspiracy thinking” for everyone else.

The Imhoff Cluster: Ten Papers, One Trait Machine

For this article I treat a decade of Imhoff-linked work as a single object: the Imhoff cluster. It’s ten papers, running from the first “conspiracy mentality” scale to the latest plausibility and cognition work, plus the corruption and cross-cultural bridges that make the trait travel.

In order of publication:

- 2014 – “Speaking (Un-)Truth to Power: Conspiracy Mentality as a Generalized Political Attitude.”

Imhoff & Bruder, European Journal of Personality, 28(1), 25–43. DOI: 10.1002/per.1930

The origin story: conspiracy mentality defined and measured as a general political attitude. - 2021 – “A Uniform Conspiracy Mindset or Differentiated Reactions to Specific Conspiracy Beliefs? Evidence from Latent Profile Analyses.”

Frenken & Imhoff, International Review of Social Psychology, 34(1), Article 27. DOI: 10.5334/irsp.590

Uses latent profiles to ask whether conspiracism is one underlying mindset or distinct types. - 2021 – “Believe It or Not – No Support for an Effect of Providing Explanatory or Threat-Related Information on Conspiracy Theories’ Credibility.”

Meuer, Oeberst & Imhoff, IRSP, 34(1), Article 26. DOI: 10.5334/irsp.587

Tests whether adding explanation or threat cues to stories changes how credible conspiracies seem. - 2021 – “Us and the Virus: Understanding the COVID-19 Pandemic Through a Social Psychological Lens.”

Rudert et al. (incl. Imhoff), European Psychologist, 26, 259–271. DOI: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000457

A broad COVID-era review where conspiracy beliefs sit among other social-psych dynamics. - 2022 – “Malevolent Intentions and Secret Coordination: Dissecting Cognitive Processes in Conspiracy Beliefs via Diffusion Modeling.”

Frenken & Imhoff, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 103, 104383. DOI: 10.1016/j.jesp.2022.104383

Breaks belief judgements into reaction-time parameters to locate in micro-cognition. - 2022 – “Conspiracy Theories Through a Cross-Cultural Lens.”

Imhoff, Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 5(3), Article 8. DOI: 10.9707/2307-0919.1175

A narrative overview of how conspiracism looks across cultures, plugging the trait into a global frame. - 2023 – “Suspecting Foul Play When It Is Objectively There: The Association of Political Orientation With General and Partisan Conspiracy Beliefs as a Function of Corruption Levels.”

Alper & Imhoff, Social Psychological and Personality Science, 14(5), 610–620. DOI: 10.1177/19485506221113965

Maps ideology, corruption indices and conspiracy mentality across 23 countries. - 2023 – “Don’t Trust Anybody: Conspiracy Mentality and the Detection of Facial Trustworthiness Cues.”

Frenken & Imhoff, Applied Cognitive Psychology, 37, 256–265. DOI: 10.1002/acp.3955

Links trait conspiracism to how people read (or misread) trust cues in faces. - 2022 / in press – “Tearing Apart the ‘Evil’ Twins: A General Conspiracy Mentality Is Not the Same as Specific Conspiracy Beliefs.”

Imhoff, Bertlich & Frenken, Current Opinion in Psychology, 46, Article 101349. DOI: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101349

Argues that the general mindset and concrete conspiracy beliefs are related but not identical. - 2024 – “Are Conspiracy Beliefs a Sign of Flawed Cognition? Reexamining the Association of Cognitive Style and Skills With Conspiracy Beliefs.”

Imhoff, Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 5(6). DOI: 10.37016/mr-2020-168

Revisits the story and folds conspiracy beliefs into a broader factor.

Together, these ten outputs are define what I call a conspiracy trait machine: the scales, profiles, process models, corruption maps, cross-cultural frames and plausibility filters that now define what “conspiracy thinking” is supposed to be – and that the rest of this article pulls apart.

BUILDING THE TRAIT MACHINE: FROM “CONSPIRACY NUTS” TO A CLEAN MINDSET SCORE

The whole machine starts with a simple but brutal reframe: “conspiracy mentality” as a general attitude toward hidden plots by powerful groups, captured in a handful of survey items. In the early scale work, diffuse suspicion of institutions is condensed into statements like “Powerful people pull the strings behind the scenes” or “Politicians usually do not tell us the true motives for their decisions”. Agreeing with these isn’t treated as a claim about any concrete scandal; it’s treated as evidence of a stable psychological property of the person endorsing them. Suspicion stops being, first of all, a claim about the world and becomes, first of all, a feature of your personality.

What the Imhoff cluster does is treat that move not as a one-off curiosity but as step one in a staircase whose direction never really changes. Step two is the latent-profile work. Here, respondents are divided into data-driven classes based on how much they endorse a wide range of conspiracy items. The profiles that emerge are reassuringly simple: mostly low, medium and high endorsement across the board. You could use the same machinery to hunt for content-based “types”—people who believe geopolitical plots but not pharma plots, say—which would push you back toward history and institutions. Instead, the findings are read as confirmation that there is one underlying dimension of conspiratorial suspicion. Different stories, same dial.

Step three asks: “Do stories themselves still matter?” In the experimental papers, threat and explanation are cranked up or down in specific conspiracy narratives, then those narratives are shown to people with different conspiracy mentality scores. When the numbers come back, narrative tweaks barely move credibility, while the trait score does most of the work. Structurally, that’s a fork in the road. One path would say: “Maybe we’re not manipulating the right content,” or “maybe context and history are carrying the weight.” The cluster takes the other path: “who you are” on the mindset axis matters more than what the story says. The locus of explanation shifts decisively inside the individual, away from the behaviour of institutions.

Step four is about normalising the whole thing. In the political-attitude mapping work, conspiracy mentality is dropped into the standard survey battery: left–right self-placement, trust in institutions, prejudice, personality traits. Once it sits there in a neat row of Likert scales, it stops looking like a category error and starts looking like just another attitude dimension—no more philosophically loaded than authoritarianism or social dominance. In parallel, process-modelling papers decompose “conspiracy decisions” into diffusion-model parameters—bias, caution, drift rates—so you don’t just have a conspiracy mindset score, you have technical parameters under the hood. Contesting the construct starts to look, from the outside, like you “don’t understand the models”.

Seen together, the shape is straightforward:

- Definition: suspicion of power is renamed as “conspiracy mentality”, a generalised trait.

- Measurement: scales, latent classes and increasingly complex models give it numbers, categories and parameters.

- Implicit intervention: once people can be scored, they can be sorted, monitored and eventually targeted—whether by “resilience” programmes, platform policies, or any governance layer that decides to import the gauge.

By the time you reach the later Imhoff papers in this cluster, “conspiracy nut” has been turned into a clean, exportable metric: a mindset score that’s been statistically stress-tested and anchored in the political-psychology canon. In other parts of the literature, including some of Imhoff’s own later work, the rhetoric around that knob softens—more talk of plausibility, context, corruption. But here, in the trait-machine phase, the point is simpler and less forgiving: the knob exists, it has been calibrated, and nothing in this part of the staircase encourages you to ask whether some of the “excess suspicion” it records might be legally or politically justified. Once the gauge is built, it’s ready for any dashboard that needs a slider marked “too suspicious of hidden coordination”.

MEASUREMENT AS RITUAL: HOW PSYCHOLOGISTS PURIFY DISTRUST

The Imhoff cluster doesn’t just measure things; it performs the same ritual over and over until messy political distrust looks like a tidy set of numbers.

The sequence always starts in the same place: with people who are suspicious of something concrete—governments, corporations, secret services, pharma, climate deals, wars, trade agreements. In the studies, those specifics show up as examples or scenario prompts, but they don’t stay on stage. Step one in the ritual is to strip out the content and the history. What matters is not which scandal or covert deal you’re worried about, but whether you agree with statements like:

“Many very important things happen in the world which the public is never informed about.”

or:

“Politicians usually do not tell us the true motives for their decisions.”

That shift—from particular allegations to vague claims about “powerful groups” and “secret plots”—is treated as a virtue in the later “evil twins” work: a trade-off between psychometric purity (clean, content-minimal items) and content richness (politically loaded specifics). In practice, the ritual consistently lands on the purity side.

Step two is the instrument cascade, and the Imhoff cluster gives you a full conveyor belt:

- Mindset scales—first in the original conspiracy mentality work and then reused across the cluster—turn diffuse suspicion into a single trait score.

- Latent profiles group people into classes and mostly find low / medium / high endorsement across many conspiracies, closing the door on content-based “types” that might map onto particular histories or institutions.

- Diffusion models, in the “malevolent intentions and secret coordination” paper, decompose conspiratorial judgments into reaction times and decision thresholds, wrapping suspicion in parameters (bias, caution, drift) that only model specialists can realistically contest.

- Cross-national and cross-cultural indices bolt country-level corruption scores, cultural dimensions and left–right self-placement onto the same trait, just enough “structure” to feel global and serious while keeping the believer at the centre.

- And even the field’s own conversation is pulled in: a citation-labelling exercise for the “Don’t trust anybody” article turns how later papers talk about it into “support / mention / contrast” counts—a metric of reception that doesn’t require reading a single argument.

Step three: what emerges at the other end are clean, reusable metrics—individual mindset scores, profile memberships, process parameters, country rankings, citation distributions. Those numbers can be copied into “misinformation” risk models, slid into governance decks, or used to define “high-risk” segments for resilience programmes or platform policy. Whatever mix of warranted and unwarranted suspicion people started with, the output the system cares about is: how high is this person, or this group, on the conspiracy mindset axis?

The price of the ritual is what fades out. Concrete allegations about specific agencies, companies, operations, contracts, treaties are not followed up as objects of inquiry; they reappear, at best, as country-level corruption indices or as generic “targets of belief” in survey items. Even where later work concedes that some conspiracies might be plausible or understandable in corrupt contexts, the explanatory weight stays on the disposition of the believer, not on the behaviour of the institution. The object of knowledge throughout is the believer’s score, bias, culture and ideology.

At each fork, the cluster makes the same choice. Between rich content and clean distributions, it chooses purity. Between reading texts and automating labels, it chooses automation. Between modelling micro-cognitive processes and dwelling on macro-structural conditions, it chooses micro-process and adds structure as a control variable. That is what makes this a ritual rather than a neutral toolkit: the choreography stays fixed even when the dataset and co-authors change.

Seen this way, the Imhoff cluster functions as a supply line: a place where distrust is routinely washed free of its concrete targets and returned as a set of mindset scores, parameters and indices—exactly the kind of numbers that can travel into dashboards and policy slides whenever someone decides that suspicion of power should be treated as a variable to be monitored, nudged and, if necessary, cut down.

WHEN CORRUPTION IS “OBJECTIVELY THERE”: DUAL TEMPLATES FOR SUSPICION

So what happens to the trait machine when there really is foul play in the system—when corruption is “objectively there”, not just imagined? The cross-national work in the Imhoff cluster gives a neat answer, and it’s a classic dual template.

In plain terms, the key pattern looks like this:

- Across countries, right-wing respondents score higher on conspiracy mentality on average (with some datasets showing a curvilinear “extremes are higher” pattern, but the practical takeaway is the same: suspicion is framed as asymmetrically clustered on the ideological right).

- Once you add country-level corruption indices, something else happens: in high-corruption environments, suspicion of hidden coordination rises across the spectrum and the left–right gap shrinks.

The models don’t just report this; they interpret it. In the text, higher conspiracy mentality among right-leaning citizens in low-corruption systems is taken as evidence of a distorted worldview, while in corrupt systems elevated suspicion is described as more understandable. Put differently, the same regression quietly mints two reusable narratives that depend on where you stand on the corruption ladder.

- Template A—“Clean” systems

In low-corruption, high-trust settings—think core EU—the trait stays centre stage. High conspiracy mentality is something about the person: an exaggerated tendency to see hidden coordination where there isn’t any, more common on the right. Suspicion of covert dealings is an overreaction, given how clean the system is assumed to be. - Template B—“Dirty” systems

In high-corruption settings, the same models concede that suspicion is, in a sense, understandable—everyone’s mindset scores climb. But they still treat that suspicion as a manifestation of conspiracy mentality under harsh conditions, with corruption entered as a contextual moderator. The unit of analysis remains the individual mindset; corruption tweaks the curve, it doesn’t displace the trait as the main story.

That’s a dual template in regression form: “irrational right-wing conspiracists in clean democracies” on one side, and “understandable but still trait-shaped suspicion in corrupt states” on the other—both routed through the same conspiracy-mindset grammar. Corruption shows up as a country-code coefficient, not as a dossier of specific operations or actors; the outcome of interest is always how conspiracy mentality behaves, not what institutions actually did.

The rest of the cluster slots into this arrangement. The cross-cultural work adds cultural values and inequality as extra knobs. The plausibility and “unwarranted belief” papers specify which suspicions can still be classed as cognitive defects even in corrupt settings—mainly the implausible ones and those bundled with a broader tendency to endorse unfounded claims. None of that breaks the templates. It just gives officials, platforms and think-tankers more caveats and sliders to sound sophisticated while they keep treating suspicion of power as primarily a psychological variable.

Who benefits from this is not hard to see. Multilateral and EU centres get a conspiracism risk map keyed to ideology and governance scores: where the “over-suspicious right” lives in clean systems, and where “understandable but still risky suspicion” sits in corrupt ones. They can talk about justified distrust in high-corruption contexts without needing to name, investigate or prosecute specific conspirators. And in “clean” contexts, they get a ready-made story about problematic, over-suspicious publics that drops neatly into resilience programmes, media campaigns and platform partnerships.

The net effect is a familiar trick in a new technical wrapper: acknowledge enough structural rot to stay credible, then route the whole problem back into individual traits and attitudes. Imhoff’s corruption work does that with equations—a dual template for suspicion that always leads back to the same dial.

THE PLAUSIBILITY TRAP: “SOMETIMES THEY’RE RIGHT” (BUT YOU’RE STILL THE PROBLEM)

Once the trait machine is built and the corruption templates are in place, the obvious objection is simple: sometimes conspiracies are real. Sometimes people really are right to be suspicious. The later Imhoff-circle papers are what happens when that critique finally lands. On the surface, they look like a correction. Underneath, they’re an upgrade.

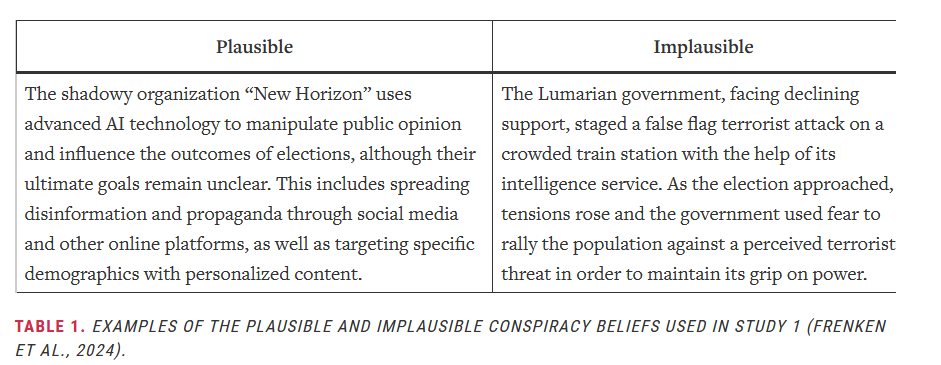

The first move is the plausibility filter. In the paper with the long title—“Just Because It’s a Conspiracy Theory Doesn’t Mean They’re Not Out to Get You”—Marius Frenken, Annika Reusch and Roland Imhoff split conspiracy beliefs into “plausible” and “implausible” sets and ask how they relate to thinking style and cognitive ability. They don’t define plausibility philosophically; they operationalise it. In Study 1, a pilot sample of German students rates a pool of fictitious conspiracy scenarios on plausibility; from those ratings, the authors pick a small set that are “consensually plausible” and another set that are “consensually implausible”. In Study 2, they then manipulate supporting information to make a scenario look more or less plausible in a belief-updating task.

In Study 1, this isn’t just an abstract split; it comes with concrete stories. One of the “plausible” vs. "implausible" items reads like this:

To a small pilot of German students in the 2020s, that classification makes sense: AI-driven manipulation by a shadowy group feels like a realistic cyberpunk-adjacent threat; a government staging a false-flag terror attack at a train station feels like movie material. But structurally, the “implausible” scenario is almost a textbook description of Operation Northwoods—a declassified 1962 Pentagon plan in which the US Joint Chiefs of Staff proposed staging or simulating terrorist attacks, hijackings and bombings, blaming them on Cuba and using the resulting fear to justify military action.

In other words, the pilot didn’t just rate stories; it quietly encoded which kinds of real historical behaviour by powerful institutions are allowed to count as “everyday knowledge” and which are relegated to the “too far-fetched” bin. The plausibility line is not drawn by a court, a truth commission or a declassification board; it’s drawn by a local consensus that hasn’t been told about Northwoods-type operations, and that consensus is then treated as the standard against which citizens’ judgements are scored.

Notwithstanding the authors’ acknowledgement about generalisability limits to Western contexts, once that line is drawn, the punchline is simple: a general suspicious mindset (conspiracy mentality) is associated with higher perceived plausibility for both sets, but the association is much stronger for the “implausible” ones, and cognitive skills are only negatively related to judging those implausible scenarios as plausible. That’s framed as nuance: we shouldn’t smear all conspiracy beliefs as irrational; the real cognitive problems sit with the extreme, far-fetched stuff.

The second move is the unwarranted belief factor. When the same group folds in other strange, obviously false non-conspiracy items, they find a higher-order “unwarranted belief” tendency that explains much of what older work treated as a special link between conspiracy belief and nasty outcomes like anti-democratic attitudes. Once you partial out that general credulity factor, the scariest conspiracism correlations shrink. Again, this is sold as sophistication: the problem isn’t specifically “conspiracy thinking”, it’s a broader epistemic style, and conspiracism is just one flavour of it.

Put back into plain language, the combined package sounds like this:

“We now admit that some conspiracies can be real or at least plausible—especially where institutions are corrupt.”

“But your habit of seeing too many conspiracies, especially the implausible ones, still tells us something about your cognitive style. The real issue isn’t that you distrust one particular institution; it’s that you show a general tendency to endorse unwarranted claims.”

That is the plausibility trap. Conspiracy belief is no longer the lone villain; it’s dissolved into a broad credulity soup. On one level, that looks fairer: suspicions about climate policy or surveillance sit alongside miracle cures and numerology. On another level, it’s extremely convenient. A whole class of politically sharp suspicions gets reclassified as just one instance of a general “unwarranted belief” problem—something that can be scored, mapped and managed across samples, countries and interventions.

At that point, the hinge question isn’t “are they distinguishing plausible from implausible?” It’s: who decides where that line sits?

In the Frenken–Imhoff setup, plausibility is whatever a small, local pilot sample says it is: German university students rating fictitious scenarios. The “plausible” side ends up being conspiracies that fit everyday common sense; the “implausible” side is whatever that group finds far-fetched. That is not a neutral boundary. It bakes in current institutional reputations, media priors and the simple fact that many real covert operations are still classified or obscure.

Take the Northwoods example again. In 1962, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff signed off on a top-secret proposal to stage or simulate terrorist attacks against US targets—including bombings, hijackings and the sinking of a US ship—and blame them on Cuba to justify an invasion. The plan was presented to the Secretary of Defense and rejected by President Kennedy; the documents sat classified until the late 1990s. For decades, telling people “the Pentagon once drew up a plan to blow up American targets and blame Castro” would have sounded like pure tinfoil. After declassification, it became a documented piece of Cold War history.

From the point of view of a 1965 “plausibility pilot”, Northwoods-style allegations would almost certainly have landed in the “implausible” bucket. From the point of view of someone who has seen the declassified memorandum, they are simply true. Nothing in the lab’s operationalisation of plausibility captures that time lag between covert planning and public documentation. Nothing in the trait models gives citizens a structured way to say: “Given what we now know about Northwoods-type operations, my prior on similar accusations isn’t a cognitive defect, it’s an update.”

So by the time the plausibility filter and unwarranted-belief factor are in place, the hard questions are no longer technical, they’re political:

- Who gets to fix the reference class of “implausible” conspiracies? A pilot of local students? Editorial consensus? Security-cleared investigators?

- What institutional checks exist on those decisions? In the models, plausibility is an input, not a contested outcome; there’s no built-in mechanism for revising classifications when new evidence (or declassification) arrives.

- What happens when platforms, police or courts start leaning on this framework? Once your profile is tagged as “high in unwarranted belief” and your specific suspicion gets dropped into the “implausible” set, it becomes very easy to discount your claims about covert coordination—even when you’re talking about actors with a proven record of doing exactly that.

Seen through that lens, the plausibility upgrade doesn’t dismantle the trait machine; it tightens it. It gives psychologists, platforms and ministries a softer line—“we don’t pathologise all conspiracies, only the implausible ones”—while leaving the basic hierarchy untouched. “Real conspiracies” are, by default, what official processes eventually certify. Everything that hasn’t crossed that threshold can be quietly parked under unwarranted belief, and the people who keep pressing those lines can be treated as problems of style and cognition rather than as political interlocutors asking whether today’s Northwoods is still locked in a safe.

WINNERS, LOSERS, AND THE PEOPLE WHO NEVER MAKE IT INTO THE MODEL

Once you’ve built a trait machine, wrapped it in corruption templates and tightened it with plausibility filters, the question stops being “what do the models say?” and becomes “who do they serve?” The Imhoff cluster never spells that out, but the actors it centres, the variables it tracks, and the absences it treats as normal make the winner–loser map fairly easy to sketch.

Winners: the people who get to use the gauges

Imhoff and the CTT guild

At the top sit the people who design and maintain the instruments. Across the cluster, the same circle reappears as authors, reviewers, scale custodians: writing the items, testing invariance, defining “plausible” vs “implausible” conspiracies, publishing verdicts on whether conspiracy beliefs are signs of “flawed cognition” or just another attitude. Once suspicion of power has been turned into a mindset score and folded into a broader “unwarranted belief” factor, this guild becomes a gatekeeper of legitimate suspicion.

If a ministry, platform or foundation wants an expert on “why people believe conspiracy theories” or “how to build societal resilience”, it will almost certainly pick someone from this world—someone whose toolkit starts from the assumption that the primary thing to study is the believer’s psychology, not the institution’s behaviour.

Platforms and policy units

Next are the actors who live on dashboards: tech platforms, “misinformation” units, behavioural science teams. The cluster gives them exactly the kind of objects they can plug in:

- individual trait scores

- cross-national tables linking conspiracy mentality to ideology, education, corruption

- parameters from diffusion models

- citation labels (“support”, “mention”, “contrast”) that can be treated as reception signals

You don’t have to read a witness statement or a leak; you can point to an “evidence-based” mindset gauge, combine it with an unwarranted-belief index and say: this segment is cognitively vulnerable and prone to conspiratorial narratives. Whether you’re tweaking a recommender, adjusting de-ranking rules or designing a “resilience” campaign, the Imhoff metrics slide cleanly into your risk models.

EU and allied governance

At the supranational layer, the corruption-moderation work and cross-cultural reviews double as cartography of distrust for European and allied institutions. They offer country-level profiles: how conspiracy mentality varies with perceived corruption, how it interacts with left–right placement, how it sits alongside institutional trust. They also offer storylines:

- in “clean” states, conspiracism clusters on the right and signals a problematic mindset;

- in “dirty” states, suspicion is understandable but still trait-shaped and in need of management.

That’s valuable if you’re allocating “democratic resilience” funds, drafting disinformation strategies, or defending institutional legitimacy under strain. The models don’t tell you how to prosecute corruption; they tell you where and how to talk about distrust.

Losers: the people who get measured by the gauges

Whistleblowers, rights advocates, investigative journalists

Flip the frame and ask: what is missing? Nowhere in the cluster is there a variable for “institutional track record of lying”, “number of validated scandals”, or “whistleblower accuracy over time”. There are no models where the key outcome is “did this agency actually do what was alleged?” The stable objects are beliefs, mindset scores, unwarranted-belief tendencies.

Anyone whose role depends on sustained suspicion—an investigator who has seen twenty cover-ups, a rights lawyer working against a dirty security service, a journalist following covert ops—has exactly one place to land in this architecture: high on conspiracy mentality. Their dossiers and institutional memories are flattened into a style of thinking.

Populations in genuinely abusive or corrupt environments

The same compression hits whole societies. In the corruption-moderation models, countries with everyday bribery, police violence or captured courts appear as lines in a multilevel regression: higher corruption index, higher mean conspiracy mentality, smaller left–right gap. Analytically interesting; structurally, the direction of explanation barely moves. Corruption is a level-2 context; the main show is still the trait.

People for whom distrust is a survival skill—because politicians really do steal, judges really are bought, foreign lenders really do dictate policy—are recorded as having high conspiracy mentality under harsh conditions. Their experience becomes contextual noise around a coefficient, not a case for legal remedy or regime change.

Everyday people in intimate settings

Once suspicion is formalised as a trait, it doesn’t stay glued to geopolitics. In the broader literature orbiting this cluster, conspiracy mentality appears in work on interpersonal trust, relationship strain and “unsafe” partners: the idea that someone who is too suspicious, too consumed by political plots, may be a liability in private life.

Combine that with a general unwarranted-belief dial and you get a quiet bleed-through: political suspicion can be re-described as a personality feature, something that shows up not only in how you see NATO or the IMF, but in how safe you are judged to be as a partner, parent or employee. That spillover is not Imhoff’s choice alone, but his instruments make it technically easy.

The people who never make it into the model

There is also a third group: those who simply don’t exist in this architecture. There is no slot for organised victims’ groups documenting state crimes; no variable for journalists who turned out to be right about surveillance programmes; no way to represent “citizens with a justified hostile prior because of Northwoods-type histories”.

When this world looks at a landscape, what comes into focus are scores, correlations and country lines. The people who did the leaking, the organising, the archive work that turned “implausible” allegations into documented fact are off-screen.

Procedural power: how this plays in law and governance

None of this needs a smoky-room conspiracy to matter. The form of the outputs—scales, parameters, risk segments—makes them highly portable into arenas where stakes are much higher than survey statistics. Tribunals, inquiries, sanctions committees and corporate investigations increasingly lean on expert evidence about credibility, bias and cognitive vulnerability.

In that context, a psychometric profile reading “high conspiracy mentality, high unwarranted belief” is a gift to any lawyer or commissioner who would rather not wade through the substance of an allegation. You don’t have to ban inconvenient witnesses; you can write, quite calmly:

“This witness has a documented tendency to see conspiracies where there are none; their testimony should be weighed with caution.”

The burden shifts, almost invisibly, from “did this institution do what is alleged, under which law?” to “what is the psychological style of the person making the allegation?” Even if no tribunal ever formalises that step, the tools the Imhoff cluster has built are perfectly suited to enable it.

If the trait machine has winners, they are the actors who calibrate and deploy the gauges: the CTT guild, platforms, and governance bodies that need to domesticate unrest. The losers are the people who end up on the wrong side of the dial, or who never show up in the model at all—the ones for whom suspicion of power is not a hobby or a cognitive quirk, but a hard-earned response to how the world has actually behaved.

ESCAPE HATCHES AND INTERNAL CONTRADICTIONS: HOW THE SYSTEM STAYS SELF-SEALING

By the end of the Imhoff cluster, the surface story is “more nuance”: not all conspiracies are irrational, corruption and crisis matter, culture matters, belief styles overlap. That is genuinely better than the old “everyone who says conspiracy is crazy” reflex.

Underneath, though, you keep hitting the same pattern: a set of structured tensions that make the framework hard to dislodge. When one line of justification is challenged, another is ready to take its place—without ever letting go of the core move that suspicion of power lives, first and last, in the believer’s head. That’s not simple sloppiness; it’s what happens when you build a flexible toolkit and never revisit its starting assumptions.

You can see it through four main fractures.

1. One mindset vs. many conspiracies

Early and mid-cluster work treats conspiracy items as “expressions of a general conspiracy mindset”. Latent-profile and scale papers mostly find that people differ in how strongly they endorse conspiracies, not which kinds they endorse. That’s the purity move: one latent disposition, one dial to calibrate.

Later, the “evil twins” pieces explicitly concede that “general conspiracy mentality is not the same as specific conspiracy beliefs”: the trait doesn’t fully capture the structure of particular narratives. The plausibility work adds that beliefs “differ in their epistemic status” and shouldn’t all be thrown in one basket.

So you get a zoom switch:

- When a single dial is useful—cross-country maps, mindset scores, headlines—the one mindset framing is foregrounded.

- When critics say “you’re treating all conspiracies as equal”, the system zooms in: now it distinguishes plausible vs. implausible, general mentality vs. specific claims.

What never gets reopened is the deeper question: whether some clusters of concrete allegations should leave the mindset frame entirely and be treated as claims about institutions, not as items on a personality-style scale.

2. Pathology vs. “just another attitude”

In one mode, conspiracism sits right next to antisemitism, prejudice, authoritarianism and cognitive deficits. Papers ask whether conspiracy beliefs are “a sign of flawed cognition”, and results stress that people high in conspiracy mentality underweight disconfirming information and cling more strongly to discredited narratives. That’s the quasi-pathology face: a mindset with built-in processing flaws.

In another mode, especially in political-attitude mapping, the same construct is described as a “normal political attitude dimension”—just one scale in a row alongside left–right self-placement and trust in institutions. Here the message is: we’re not diagnosing anyone; we’re just measuring a way of seeing politics.

Both moves have real value. Slotting conspiracy mentality into the ordinary attitude battery does reduce crude pathologising; spelling out biases does catch some truly sloppy reasoning. But together they give the system two faces:

- Need to talk about extremism, radicalisation, “unsafe” partners, democratic backsliding? → put on the pathology face.

- Accused of stigmatising dissent? → flip to the “just another attitude” face.

The contradiction isn’t resolved; it’s repurposed as flexibility.

3. Trait-first vs. corruption, crisis and culture—and who defines “corruption”

The cross-national work is not blind to context. In Suspecting Foul Play When It Is Objectively There, Alper & Imhoff show that in countries with higher corruption scores, suspicion of hidden coordination rises everywhere and the right–left gap shrinks. They explicitly say that in such places, conspiracy beliefs can be more “rational” responses to “valid cues”. This is a real upgrade on pure “paranoid mind” talk.

But two things are locked in:

- Corruption stays a moderator, not a rival explanation.

Corruption, crisis and culture enter as level-2 variables that shape how the trait expresses, but the explanatory centre of gravity stays on conspiracy mentality as an individual difference. Even when suspicion is called “understandable”, the solution space still points back to adjusting the trait, not the institutions. - “Corruption” is defined elsewhere.

Country scores don’t come from trawling lobbying registers or declassified archives; they’re imported from global perception indices built from business and expert surveys. Those tools are good at classic bribery and petty public-sector abuse, but they largely normalise legalised corruption in Western democracies: lobbying as “interest representation”, dark money as “independent expenditure”, revolving doors as “career mobility”.

That means:

- Countries like Germany, the Netherlands or the US sit at the “low corruption” end by construction, even with heavy access money and revolving doors.

- Countries with more overt or petty corruption pile up at the “high corruption” end, often poorer, non-Western states.

Once these values are treated as “objective cues”, the trait machine is primed to say:

- In “clean” systems → high conspiracy mentality, especially on the right, is over-suspicion, a mindset problem.

- In “dirty” systems → suspicion is understandable, but still processed as the same trait under harsher conditions.

Technically, that’s context-sensitive modelling. Structurally, it’s Western-centric priors baked into the ground truth: indices decide where corruption officially “lives”; the trait model then decides whose suspicion is irrational against that backdrop.

4. Unique danger vs. one flavour of credulity

One stream in the cluster leans into conspiracism as a special risk. Higher conspiracy mentality is tied to anti-democratic attitudes, prejudice, norm-breaking; these links are presented as potential threats to democratic stability. That version travels easily into policy and media.

The unwarranted-belief work then partially pulls this back. When you add obviously false non-conspiracy items, a broader “unwarranted belief” factor appears. Imhoff & Bertlich show that once you control for general credulity, the strongest conspiracism–anti-democracy links shrink. Frenken et al. find cognitive variables relate substantially to judging implausible conspiracies as plausible, far less to plausible ones.

On the generous reading, this really does avoid over-pathologising political suspicion: much of the trouble sits with far-fetched, across-the-board credulity. On the structural reading, it creates another double track:

- Need urgency? → Conspiracism is uniquely dangerous, a red flag for democracy.

- Accused of targeting dissent? → Conspiracism is just one flavour of unwarranted belief; the “real” issue is a general epistemic style.

No one asks whether some “conspiracies” in the item pool belong, not in a credulity factor, but in a history book.

Plausibility, corruption and who sets the yardsticks

Underneath sits the paired question the papers almost never foreground:

- Who decides which conspiracies are plausible?

- Who decides which systems are corrupt?

In Frenken, Reusch & Imhoff, plausibility is set by a pilot of German students rating fictitious scenarios. A shadowy AI-driven propaganda outfit is classed as plausible. A government–intelligence false-flag terror plot at a train station—functionally a Northwoods clone—is classed as implausible. In reality, Operation Northwoods shows Western militaries have drafted exactly this kind of plan. But in the lab, student intuitions become the standard for “biased plausibility judgements”.

In the corruption work, elite perception indices that treat lobbying and dark money in the West as normal politics become the standard for “objectively there”.

From that point on:

- If your suspicions line up with what Western students and CPI-style indices already believe → you look reasonable.

- If your suspicions cut against that consensus—about state crimes the pilot finds “movie-like”, or about legalised Western corruption the indices treat as clean → you look like you have high conspiracy mentality and unwarranted belief.

The nuance is real; the yardsticks are not neutral.

How the contradictions keep the system closed

Map the fractures as a decision tree and the escape hatches are obvious:

- “You’re treating all conspiracies the same.” → Invoke plausibility and evil-twin work; insist on nuance; keep the trait.

- “You’re pathologising dissent.” → Stress that conspiracy mentality is a normal attitude dimension; no diagnosis here.

- “You ignore corruption and culture.” → Point to cross-national moderation; concede “valid cues”; still interpret through a mindset lens defined by CPI-style terms.

- “Western systems are corrupt too.” → The indices have already declared them low-corruption; suspicion there remains, by construction, more mindset-like.

From inside the guild, this reads as responsible sophistication—and some of it is. Distinguishing plausible from implausible beliefs and showing that broader credulity matters does stop some over-reach. But structurally, the effect is self-sealing.

The contradictions don’t force a rethink of the trait machine. They give it multiple façades—one mindset vs. many beliefs; pathology vs. ordinary attitude; trait vs. context; unique danger vs. general credulity. Whichever line is under attack, another can be swapped in to preserve the core: that sustained suspicion of hidden coordination is best understood, and best acted on, as a psychological profile to be mapped and managed—even when history, corruption and declassified archives suggest the real problem may not be the dial in people’s heads, but the machinery they’re looking at.

THE WORLDVIEW UNDERNEATH: SUSPICION AS RISK SCORE

If you zoom out from the individual papers and look at the Imhoff cluster as one object, you don’t just see a set of methods; you see an implied world. It’s not Westphalian in the classic sense—concerned with sovereign states and formal borders—but it has its own kind of order. Call it a psychometric order: the key unit isn’t territory or jurisdiction, it’s the scored and sortable mind.

In that world, powerful institutions are not the primary objects of suspicion. States, alliances, intelligence services, corporations, treaties—they appear as background variables, country codes, corruption scores, cultural dimensions. They shape the environment, but they are almost never the thing to be investigated in their own right. The thing that is examined in high resolution is the citizen’s suspicion: first as a mindset score, then as a profile, then as diffusion parameters and unwarranted-belief factors, then as country-level averages and risk segments. “Conspiracy theories” are not treated as dossiers that might or might not be true; they are treated as symptoms of a style of thinking.

Classic international law cares about what happens behind the curtain: covert operations, collusive deals, sanctions evasion, war crimes, clandestine agreements between states and firms. Its basic question is: what did powerful actors do, under which rules, and with what evidence? The Imhoff-type framework quietly shifts the centre of attention from what is done in secret to who suspects it and what’s wrong with them. Corruption, crisis and history are allowed in as moderators and backdrops, but the analytic spotlight stays on the believer: their mindset, their plausibility judgements, their position on an unwarranted-belief axis.

Seen against the wider Mindwars line, this is the endpoint of a trajectory. The Original Sin traced the moment when “suspicion of power” was rebadged as “conspiracy mentality”—a diagnosable attitude. The Consequences Factory showed how those diagnoses feed into a broader governance stack, where risk scores and vulnerability maps guide interventions. Who’s Allowed to Say ‘Conspiracy’ dug into the asymmetry where elites can coordinate in secret as a matter of routine, but citizens who allege coordination are graded on their plausibility. The Imhoff cluster sits in the middle of that arc as a standardisation module: the place where suspicion is refined into a global, exportable metric.

You don’t have to endorse any given conspiracy theory to see the stakes. The question isn’t “are these items sometimes silly?”—many of them may well be. The question the cluster quietly answers for us is this: do we want suspicion of power to be a political claim that can be proven or disproven, or a psychological profile that can be scored and contained? The Imhoff cluster doesn’t answer that in a manifesto. It answers it in practice, by building the gauges that make one of those futures much easier than the other.

Published via Mindwars Ghosted.

Mindwars: Exposing the engineers of thought and consent.

—

Author’s Note

Produced using the Geopolitika analysis system—an integrated framework for structural interrogation, elite systems mapping, and narrative deconstruction.

Support: Mindwars Ghosted is an independent platform dedicated to exposing elite coordination and narrative engineering behind modern society. The site has free access and committed to uncompromising free speech, offering deep dives into the mechanisms of control. Contributions are welcome to help cover the costs of maintaining this unconstrained space for truth and open debate. If you like and value this work, Buy Me a Coffee