Mindwars: The NZ COVID-19 Royal Commission’s Architecture of Evasion

Decoding the New Zealand COVID-19 Royal Commission’s curtain call on ministerial public accountability.

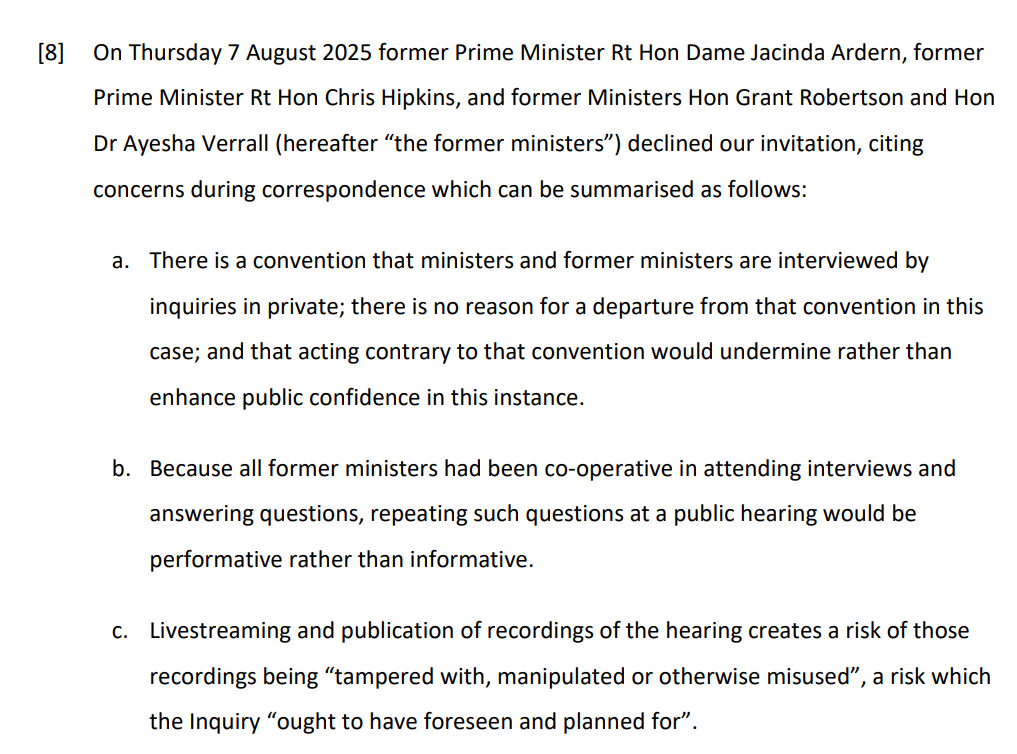

On 13 August 2025, the Royal Commission into New Zealand’s Covid-19 response released a seemingly administrative update—Phase Two, Minute 4— a terse update stipulating that senior ministers would not testify.

At first glance, this looks like procedural housekeeping, but on closer examination, it reveals the blueprint of institutional self-protection dressed in the language of fairness.

The reason? “Ministerial convention.” A phrase invoked like a constitutional spell, transforming what could have been public accountability into a politely worded administrative closure.

This isn’t just about who gets to speak. It’s about how public memory is sculpted—how the official record fixes the shape of the story for decades to come. Once the Commission’s choices are locked in, the script is immortalised like a Shakespearean play: cast set, lines finalised, ending predetermined. The audience may debate the performance, but the script itself is untouchable. In this production, the lead roles were quietly recast or written out, and it looks like the audience will never get to see the real decision-makers step into the light.

Yet livestreams and transcripts cannot compensate for the silent absences at the inquiry podium.

Transparency Without Exposure

During what was to be Week One of the public submissions, the Commission offered livestreams and published hearing transcripts. These offered the optics of openness, but the choreography is pre-set—who appears, what is asked, and which topics are safely omitted are all decided in advance. The supposed transparency is procedural theatre: visibility without access, process without friction. More on the theatrical aspect of the proceedings during that first week in my article Mindwars: A Ritual of Containment –NZ COVID-19 Royal Commission as Choreographed Theatre.

“Procedural fairness,” another guiding motif in the minute paper, is presented as a rationale for exclusion. This flips the concept on its head. In a functioning democratic inquiry, fairness often means including the hard questions and powerful figures—not shielding them.

Among the justifications floated was the claim that earlier witnesses—especially senior officials—were subjected to “unfair public criticism” after their testimony. But this reasoning collapses under minimal scrutiny. Public criticism is not evidence of procedural unfairness—it may, in fact, signal that testimony was meaningful. The suggestion that officials or ministers should be exempt from scrutiny because the public responded critically is structurally absurd. That’s the price of holding power, not an injustice.

This is not a trivial matter—but nor is it unique. Every democracy that takes public accountability seriously accepts that open hearings carry the risk of discomfort, backlash, and even hostility. To remove decision-makers from view on this basis is to set a precedent that accountability ends where discomfort begins. If the architects of pandemic policy cannot be publicly questioned without fear of reprisal, then the social contract has already frayed far beyond the reach of any commission.

It would appear that former Prime Minister Dame Jacinda Ardern and others added that their decisions had been “well documented” and “publicly explained” elsewhere.

But in camera pre-recorded statements, retrospective interviews, or political memoirs are not substitutes for a forensic inquiry process. They lack cross-examination, sequencing, and institutional framing. They are, by design, unilateral outputs—crafted for legacy, not scrutiny. When such formats are used to retroactively validate policy without challenge, they function less as evidence and more as controlled memory capsules.

The claim that ministerial testimony would “politicise the process” inverts accountability logic. Sensitive issues demand scrutiny, not insulation. A robust inquiry isn’t politicised by proximity to power—it’s neutered by its absence.

Ultimately, these deflections don’t merely protect individuals—they re-engineer the very idea of what public transparency is supposed to mean. They convert scrutiny into threat, and silence into virtue. What we are left with is a performance of inquiry, where ritual substitutes for risk, and appearance is choreographed to neutralise structural challenge.

Who Writes the Ending?

Perhaps the most revealing part of the Commission’s minute is how quietly it wraps things up. The language suggests everything is settled—the hearings are done, the decisions explained, the record closed. No confrontation, no loose ends. Just a sense that the curtain has fallen and nothing more needs to be said.

But large sections of the public don’t want a tidy ending. They want accountability. They want the people who made the decisions to front up—not through written statements or curated recollections, but in person, visible, answerable, and real. They want to watch them speak, stumble, justify, or reflect. Not because of vindictiveness—but because the act of showing up matters. It’s how trust is rebuilt—or decisively lost.

The choice not to invite senior ministers wasn’t debated. It wasn’t tested in Parliament. It wasn’t aired in advance. It was tucked into a vague discretionary clause—“where appropriate”—and deployed at the final procedural moment. That’s not neutrality. It’s narrative editing—deciding whose voice belongs in the archive and whose does not. “Ministerial convention” is a Westminster vestige dating to 19th-century cabinet confidentiality norms. Historically meant to protect collective Cabinet deliberations, in this case it becomes a procedural lockout—privileging executive comfort over forensic rigor. However, this is a Westminster inheritance, not a constitutional immovable. Its invocation here serves less as a safeguard of principle and more as a convenient shield—protecting ministers from the kind of public scrutiny they once championed in opposition.

What the public received was not clarity but choreography: a controlled narrative, carefully framed to minimise disruption. What might have been a moment of reckoning was recast as a performance of resolution—calm, closed, and conspicuously free of ministerial presence. For a commission claiming to serve public confidence, it misread what confidence demands..

Final Reflection

What the Royal Commission has offered is not a failure of process, but its optimisation—a masterclass in narrative containment. And in that efficiency, in that polished silence, lies the real story: a state that has learned how to talk without saying anything at all.

If public confidence is to be more than a buzzword, New Zealanders must demand a follow-up session in which ministers answer questions under oath—or pursue a citizen-led tribunal that cannot dodge the witness stand.

Published via Journeys by the Styx.

Mindwars: Exposing the engineers of thought and consent.

—

Author’s Note

Produced using the Geopolitika analysis system—an integrated framework for structural interrogation, elite systems mapping, and narrative deconstruction.