Mindwars: The Self-Sealing Science of Conspiracy Theory Theorists (CTTs)

An investigation into the closed epistemological loop of Conspiracy Theory Research, where institutional failure is a blind spot, and public scepticism is the disease to be diagnosed.

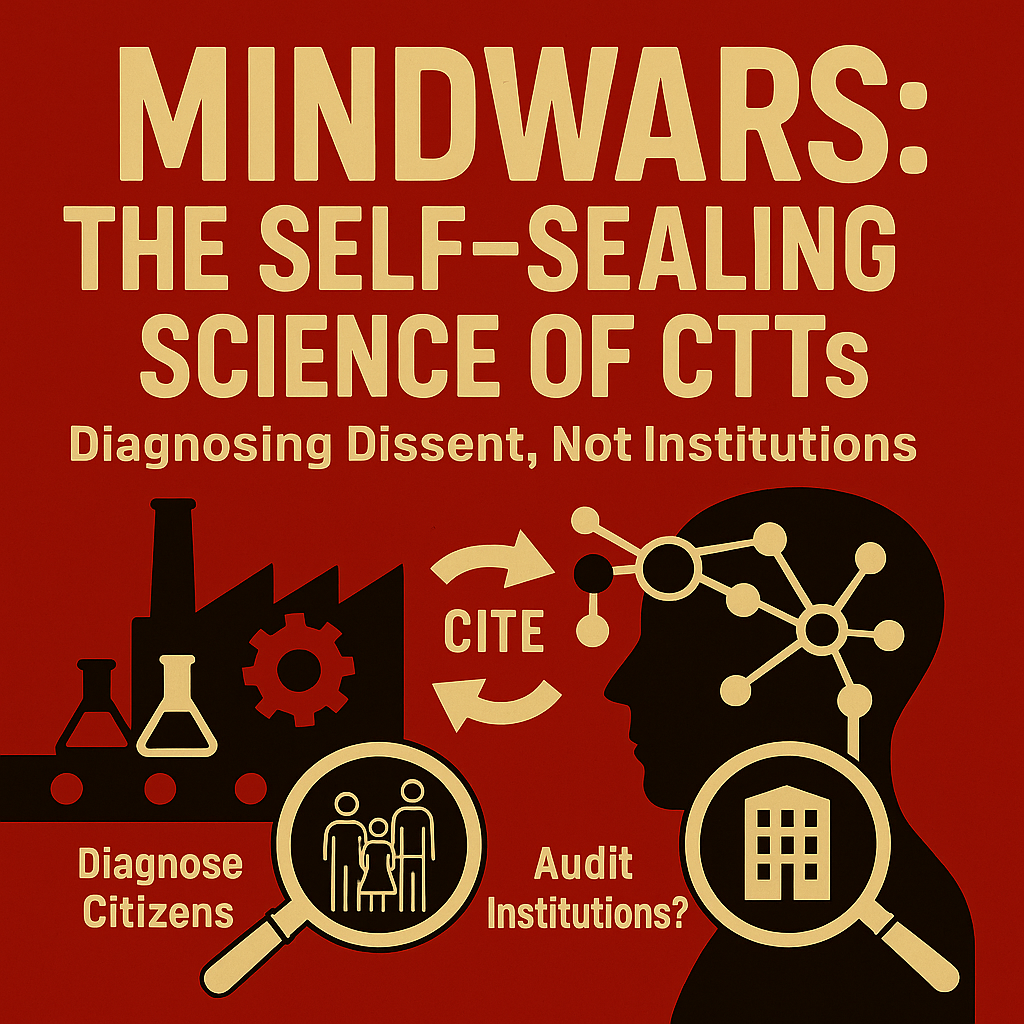

From TISP to CTT: the upstream factory

In this Mindwars series examining the works and epistemology framework of the Conspiracy Theory Theorists (CTTs) the last article, From CONSPIRACY_FX to Perceptions of Science, showed how a “neutral” 68-country survey decided what counted as legitimate opinion and exported that lens via a prestige academic consortium. That article finished in a reflection on the technocratic control and governance worldview revealed in the endeavour.

This article steps upstream to the theory layer that makes that instrument possible. We show how a corpus of six papers co-authored under Prof. Dr. Roland Imhoff’s name (listed at foot of the article) assembles that CTT worldview—a trait-first ontology sealed against content, fitted with a context valve, and expanded by a domain hop. From that frame, the TISP logic is not a one-off; it is inevitable. Imhoff was selected as a prominent researcher in one of the CTT hubs identified in the Conspiracy_FX Clusters – Who Runs the Category Factory article.

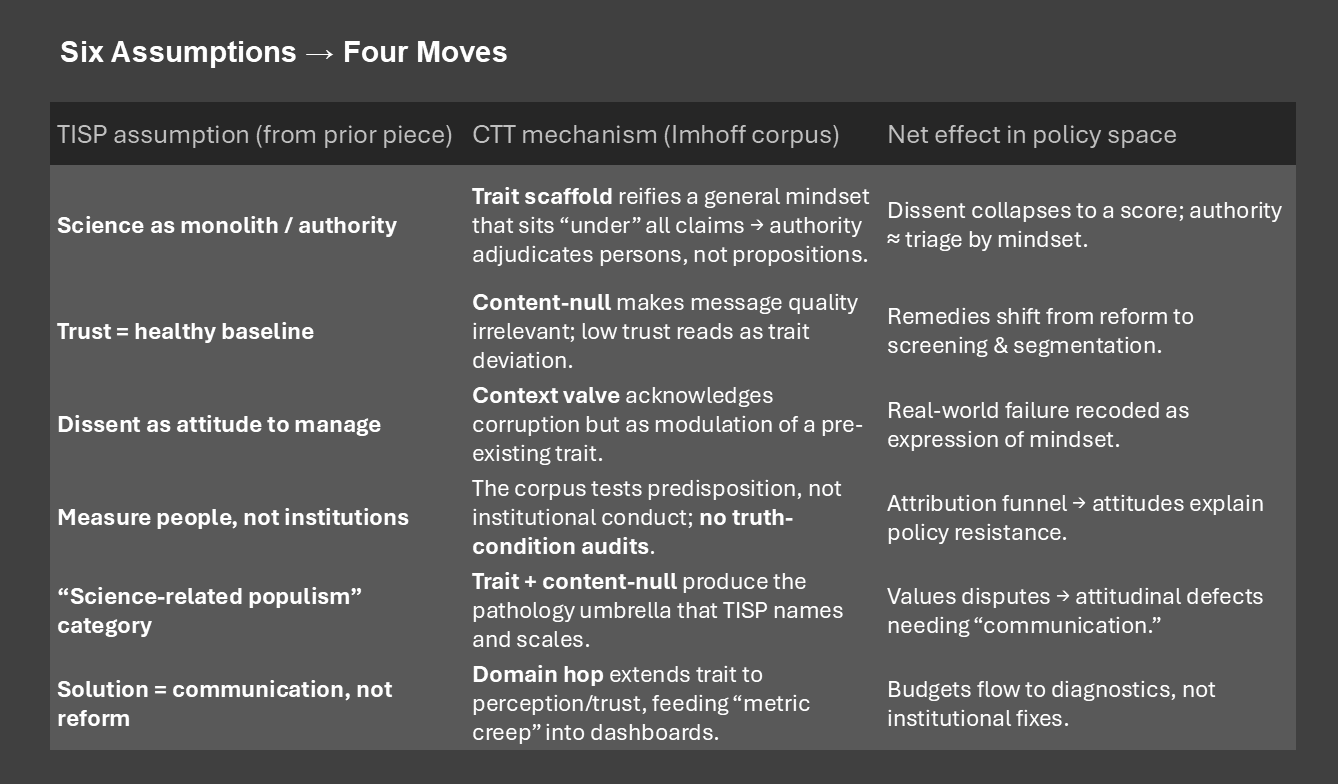

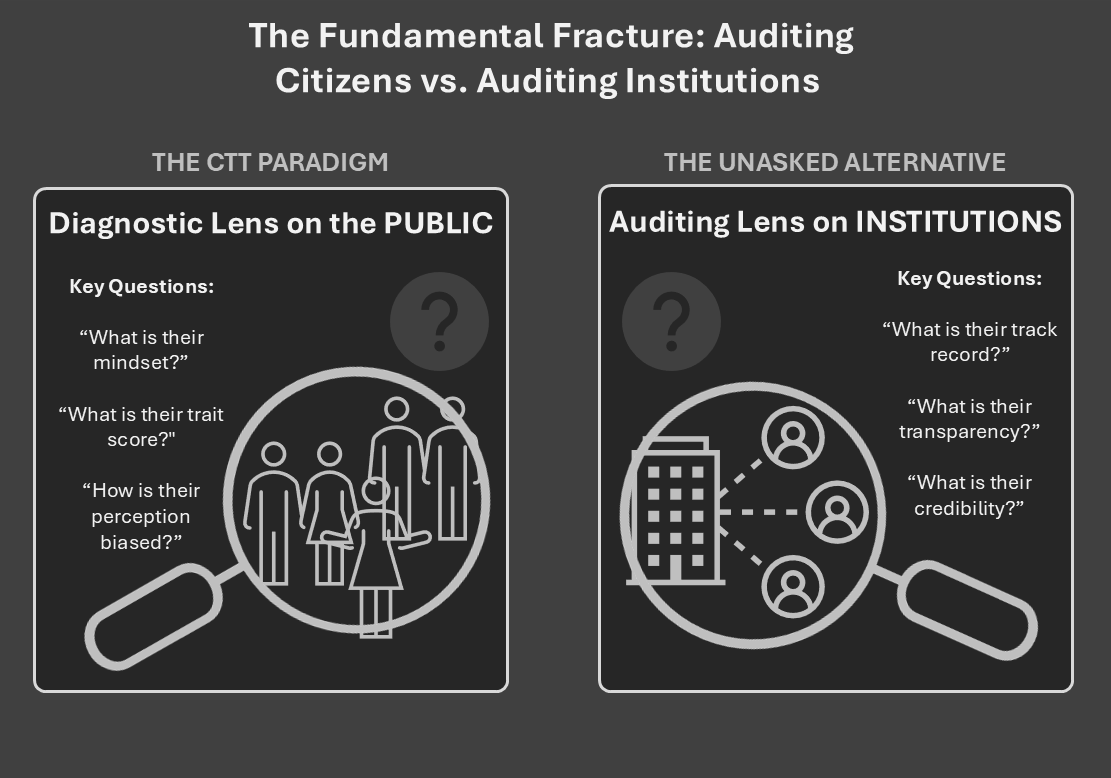

When public scepticism meets official messaging, a verdict increasingly arrives before evidence is examined: diagnose the doubter’s worldview, then dismiss the claim. In the CTT frame—exemplified by Imhoff and collaborators—this is design, not drift. The research program first constructs an ontology of a stable “conspiracy mentality,” then organises evidence inside it. From such a frame, a closed Diagnostic Loop is not malpractice; it’s output.

The frame is assembled in four moves, each with a linguistic receipt:

- Trait scaffold (LPA) — “Uniform patterns would speak in favor of a general mindset.”

- Content-null — “No mechanistic… effect of merely adding specific information; credibility only driven by predisposition.”

- Context valve (corruption) — CTs as “alarm signals… a ‘wake-up call’.”

- Domain hop (perception) — “Don’t trust anybody: … detection of facial trustworthiness cues.”

In this worldview: dissent is diagnosable, content dispensable, context absorbable, scope elastic. Where TISP performs legitimacy laundering at scale, the CTT lab stack manufactures the ontology that TISP deploys. The field’s ritualised transparency (open materials, preregistration) polices public trust while staying largely silent on its own meta-scientific fragility—replication failures and elevated false-positive baselines that rationally fuel distrust—and on realpolitik: proven institutional corruption and geopolitical reality.

This article therefore doesn’t “trace the construction of a loop” so much as expose the construction of the worldview from which the loop follows. It shows how the CTT frame predetermines interpretation, where its own data strain that frame, and what tests would force the paradigm to face contexts where institutional performance dominates trait: scope-bounded statistics, preregistered bridge mechanisms (belief → perception), context switch-points (when corruption leads), and orthogonal replications outside the author–venue network.

The Architecture of a Worldview — Six Axioms of the CTT Paradigm

The CTT program is not a neutral inquiry; it is the operational output of a prior frame. Its methods—the Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire (CMQ) and Latent Profile Analysis (LPA)—are less open-ended discovery tools than embodiments of that frame. We surface the axioms first, then show how CMQ and LPA instantiate them.

The Six Axioms:

1) Primacy of the psychological

Public scepticism is treated as a disposition, not an evidentiary or political stance “move away from concrete… to a general mindset.” The governing question shifts from “Is the claim valid?” to “What is the mindset of believers?” The field explicitly recommends moving from concrete theories to a general “mentality”—the baseline becomes mindset, not claim-truth.

2) Generality of the trait

Distrust is posited as a cross-domain mentality; suspicion in one sphere implies a general predisposition across others. The cross-cultural “workaround” is to abstract from particulars to a portable trait. The LPA setup then defines the test: “Uniform patterns would speak in favor of a general mindset.” In short: generality is both premise (CMQ design) and criterion (LPA).

3) Insignificance of content

What matters is form (an accusation against power), not evidential status. Experiments report “no mechanistic… effect” of adding information; credibility is “only… driven by… predisposition.” Content is sealed out of the causal chain; message quality becomes orthogonal to belief.

4) Presumption of institutional benignity

Official accounts function as the baseline reality. Deviation is explained psychologically rather than examined as potential institutional failure. The cross-cultural rationale centres mentality over truth-condition audits, reiterating the generic-mindset solution and sidelining institutional performance.

5) Pathologisation of distrust

Dissent is framed as a general mindset/propensity—a person-level deficit. LPA’s “uniform vs. differentiated” language stabilises the general mindset even while noting “important qualifications” or “more differentiated patterns.” Heterogeneity is acknowledged but subordinated to the trait scaffold.

6) Locus of the problem

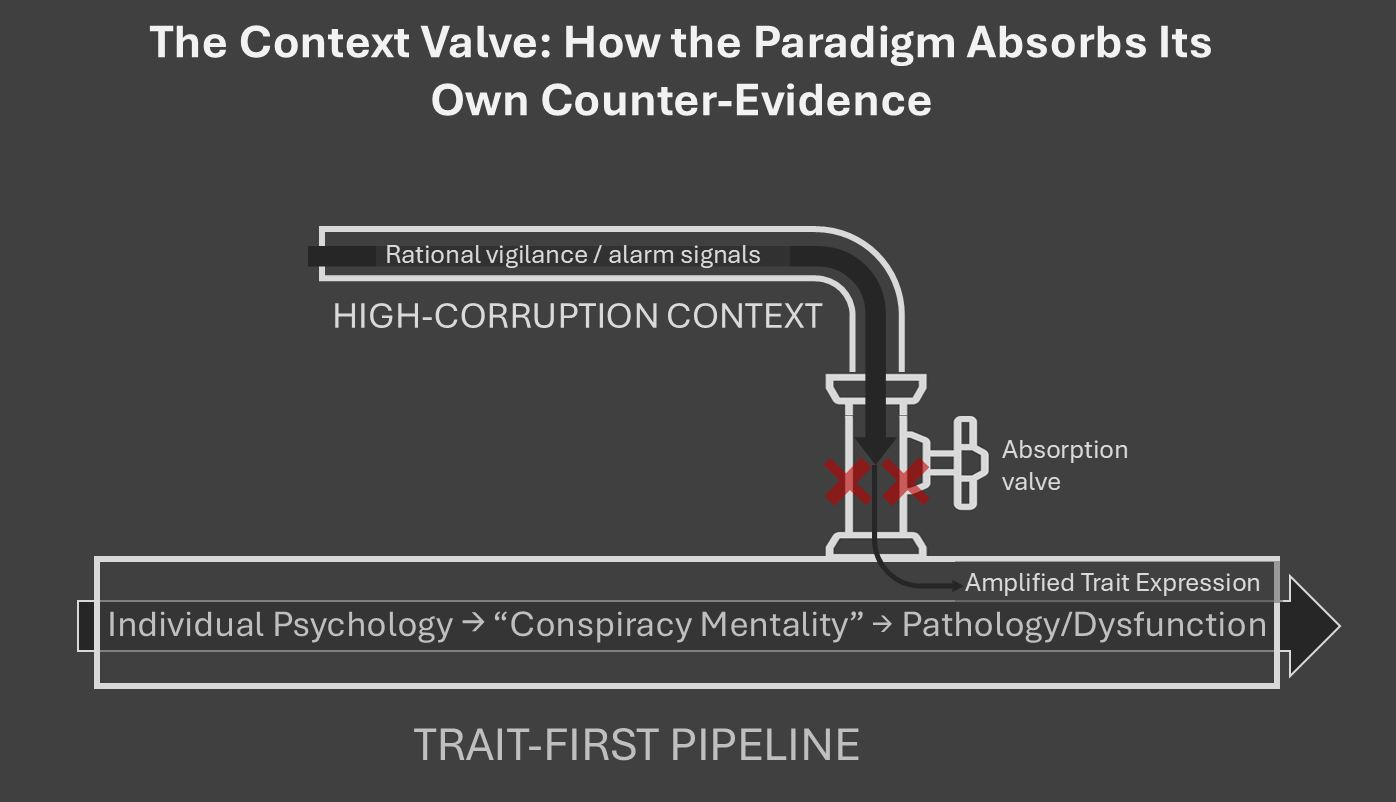

The “problem” of conspiracy beliefs is located in the individual, not in institutional conduct. Even when corruption is introduced, it is cast as modulating trait expression rather than displacing trait primacy; CTs as “alarm signals… a ‘wake-up call’” prove the context valve while keeping the lens on the person.

Worldview → Tools: How the Frame Becomes Practice

The CTT worldview does not remain abstract; it is engineered into a series of self-validating tools, moving from a diagnostic instrument to a perceptual verdict:

- CMQ (Worldview → Instrument):

The field explicitly recommends “mov[ing] away from concrete conspiracy theories to a more general mindset.” This directive materialises in the Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire (CMQ), operationalising the axioms of psychological primacy and generality—a deliberately generic instrument using decontextualised statements about secret plots. By design, it assumes a single, portable trait where suspicion of pharmaceutical companies becomes formally equivalent to belief in reptilian overlords. Content becomes secondary to form, implementing the axioms of generality and content-insignificance through its very architecture. - LPA on CMQ (Worldview → Statistic):

The methodological follow-through articulates what the CMQ implies: “Uniform patterns would speak in favor of a general mindset.” When Latent Profile Analysis is applied to CMQ data, the discovery of uniformity becomes “proof” of the very trait the instrument was designed to presuppose. The subsequent caveats about “differentiated patterns” and “important qualifications” function as ring-fenced concessions, preserving the core ontological commitment to a unified mindset despite contradictory evidence. - Seal (Content-Null):

Empirical closure arrives through experimental findings: across two studies, adding explanatory or threat information shows “no mechanistic… effect” on credibility, which remains “only… driven by… predisposition.” This seals the framework: the substance of claims becomes irrelevant, while the individual’s pre-existing trait score emerges as the sole determinant of belief. The paradigm successfully shifts focus from evaluating information to classifying people. - Hop (Belief → Perception):

The final operational move expands the construct’s jurisdiction from attitudes to basic perception. The study “Don’t trust anybody: Conspiracy mentality and the detection of facial trustworthiness cues” reframes the trait as a perceptual style—claiming those with high CMQ scores become “less sensitive” to objective trustworthiness cues. This migration from political stance to perceptual mode naturalises person-level screening as a legitimate policy tool.

The Closed Circuit: Axioms → Instruments → “Proof”

The result is a self-sealing argument: the axioms dictate the tool design, the tools produce confirming data, and that data is then presented as independent validation, so that:

- Generality is first asserted (via CMQ design), then statistically ratified (via LPA)

- Content irrelevance is built in, then empirically sealed by experimental findings

- Scope systematically expands via domain hops from beliefs to perception.

Where the Frame Strains (But Holds)

Confronted with data that challenges its core assumptions, the paradigm exhibits a key feature of a resilient worldview: it admits anomalies only to contain them, preserving the original diagnostic lens through:

- The Context Valve (Corruption): When Alper & Imhoff introduce corruption data, their findings threaten the paradigm: in high-corruption countries, ideological differences compress and conspiracy theories function as “alarm signals… a ‘wake-up call’” rather than pure pathology. Yet the discussion maintains the mindset vocabulary, containing the challenge within the trait-based framework. The implied solution remains managing individual psychology rather than addressing institutional corruption.

- Candour vs. Inertia: The LPA paper demonstrates methodological candour by acknowledging “method-related uncertainties” and limits of variable-centred models. However, this transparency changes nothing operationally—the general mindset remains the organising object of analysis. Heterogeneity is acknowledged but ontologically contained.

Bottom Line

The “conspiracy mentality” wasn’t a discovery that forced theoretical revision. It was the predetermined product of foundational assumptions—materialised through instrument design (CMQ), enforced through statistical methods (LPA), and reinforced through experimental results that the architecture itself made inevitable. The tools didn’t discover the trait; they manufactured it.

The Self-Validating Loop in Action

(Drawing from Meuer, Oeberst & Imhoff, 2021)

With the “conspiracy mindset” installed as a measurable trait, the CTT paradigm makes its pivotal move: it uses the construct to convert dissent into a diagnostic reflex. The 2021 study by Meuer, Oeberst, and Imhoff is presented as proof that scepticism is content-agnostic. But that “proof” rides on a hidden premise: that the “information” injected into the experiments is credible and relevant to receivers.

The Circular Logic of “Content-Irrelevance”

Two experiments add what researchers define as explanatory or threat-related information to conspiracy narratives. The punchline is delivered via two closure cues:

- “No mechanistic… effect of merely adding specific information…” (Closure Cue)

- “Predisposition was the only predictor.” (Closure Cue)

On paper, the paradigm is sealed. In practice, the design assumes the added information should persuade a rational observer. It never entertains the equally rational stance that dissenters might discount those inserts because they discount the source—institutions they already distrust. What the paper calls “adding information” can easily read, to participants, as “adding more institutional talking points.”

The Missing Mirror Test

If the logic is symmetric, flip it: would institutional loyalists budge if given “explanatory information” from conspiracy proponents? Almost certainly not. Yet their stability would be coded as reasonable commitment, not pathology. The asymmetry is the tell:

- Institutional loyalty = healthy baseline

- Scepticism = psychological deviation.

The Ultimate Pathologising Move

By defining their information as objectively valid and still finding no effect, researchers complete the Diagnostic Loop:

- Define scepticism as a psychological trait

- Provide information from institutionally-aligned sources

- When scepticism persists, declare it evidence of pathology.

This circular proof absolves institutions of examining why their information might be unconvincing. The problem must reside in the receiver’s psychology, because the researchers have predefined their information as objectively sound.

The Institutional Shield

This framework functions as an institutional shield. If all “credible” information comes from official or academic sources, and when scepticism persists despite this information, it implies:

- Transparency is futile — “the information won’t be believed anyway”

- Reform is irrelevant — the problem isn’t performance; it’s people

- Budgets flow to management of minds — screening, segmentation, targeted comms; not audit, disclosure, or operational fixes.

The “only-predictor” finding becomes self-fulfilling: define the problem as individual psychology, and institutions never have to confront the possibility that their credibility decline is earned.

The Real Closure

The true closure happens not in the results, but in the design. By assuming their informational content represents neutral facts rather than positioned claims, CTT researchers build their worldview into the methodology itself. The subsequent finding that “content doesn’t matter” simply reflects that their particular content doesn’t matter to people who’ve learned to distrust the institutions behind it. The loop was closed before the first experiment began.

The Cracks in the Frame: When Reality Intrudes

(Drawing from Alper & Imhoff, 2023 and Imhoff in Rudert et al., 2021)

The CTT paradigm runs on a simple engine: diagnose dissent as a mindset, then show that information doesn’t move it. But parts of the literature cut against that grain. When the papers look out at the real world—where corruption varies dramatically—their own data starts to behave like a rebuttal.

What the Theory Quietly Concedes

In cross-national work, CTT researchers make a startling concession: in settings with high corruption and low transparency, conspiracy endorsement can be a “more or less valid” reaction. They invoke Error Management Theory here—the evolutionary idea that it’s better to over-detect a threat than miss a real one. In other words, they acknowledge that under certain conditions, distrust can be adaptive.

Alper & Imhoff make this explicit, framing conspiracy theories as “alarm signals… a ‘wake-up call’” when hostile coalitions or corrupt practices plausibly exist. Suddenly we’re not talking about pathology anymore, but function.

The Corruption Corollary: The Data That Bites Back

The numbers tell a compelling story. Using data from 23 countries (N > 20,000), Alper & Imhoff show that corruption dramatically changes the conspiracy belief landscape: “corruption… attenuated ideological difference; everyone… more likely to adopt a conspiracy mentality.”

Translation: in dirty contexts, suspicion becomes common sense, not a fringe defect. The data suggests that what looks like a “conspiracy mentality” might simply be accurate threat detection in hostile environments.

...And Yet, The Paradigm Reverts

Despite these concessions, something remarkable happens in the discussion sections. The language slides back to the familiar trait lexicon—“hypersensitivity,” “bias,” “mindset.” The clear, logical prescription—fight corruption—never appears as a programmatic recommendation.

Instead, corruption gets treated as a contextual amplifier of a pre-existing flaw in people, not as a primary driver that can displace trait primacy. It’s a classic context valve—admitting reality only to contain its challenge to the core doctrine.

The Schism Exposed

This creates a fundamental tension in the CTT worldview:

- You can’t call conspiracy theories a useful “wake-up call” while maintaining that message content never matters

- You can’t frame distrust as evolutionarily adaptive while pathologising it as a cognitive defect

- You can’t show corruption makes everyone more suspicious while insisting the problem is individual psychology.

The missing questions—which the papers don’t ask—are crucial: At what level of corruption does context dominate trait? Where is the switch-point beyond which the rational baseline becomes distrust?

Why This Matters for Policy

The “alarm signal” framing implicitly licenses rational suspicion in corrupt settings. That undercuts any policy that treats skeptics as default defectives to be “corrected.” Yet the persistent mindset language nudges decision-makers back toward screening and segmentation rather than institutional reform.

The result? We get better tools for diagnosing citizens rather than cleaner governments. We develop more sophisticated surveys to measure public pathology rather than more transparent institutions that might earn public trust.

The Bottom Line

The literature admits—then systematically downplays—its most important finding: when environments are corrupt, suspicion is rational. Treating this as a mere “moderator” keeps the CTT worldview intact. Treating it as a fundamental switch would force a different science altogether: one that audits institutions at least as rigorously as it profiles individuals.

The Citational Loop and the Ioannidis Proof

(Drawing from the analysis of institutional trust and scientific integrity)

Sor far, we have seen how the CTT frame is built and defended. We now move on to explains why it’s so hard to challenge: the field operates a closed circuit, systematically avoiding a reckoning with the fragility of its own science.

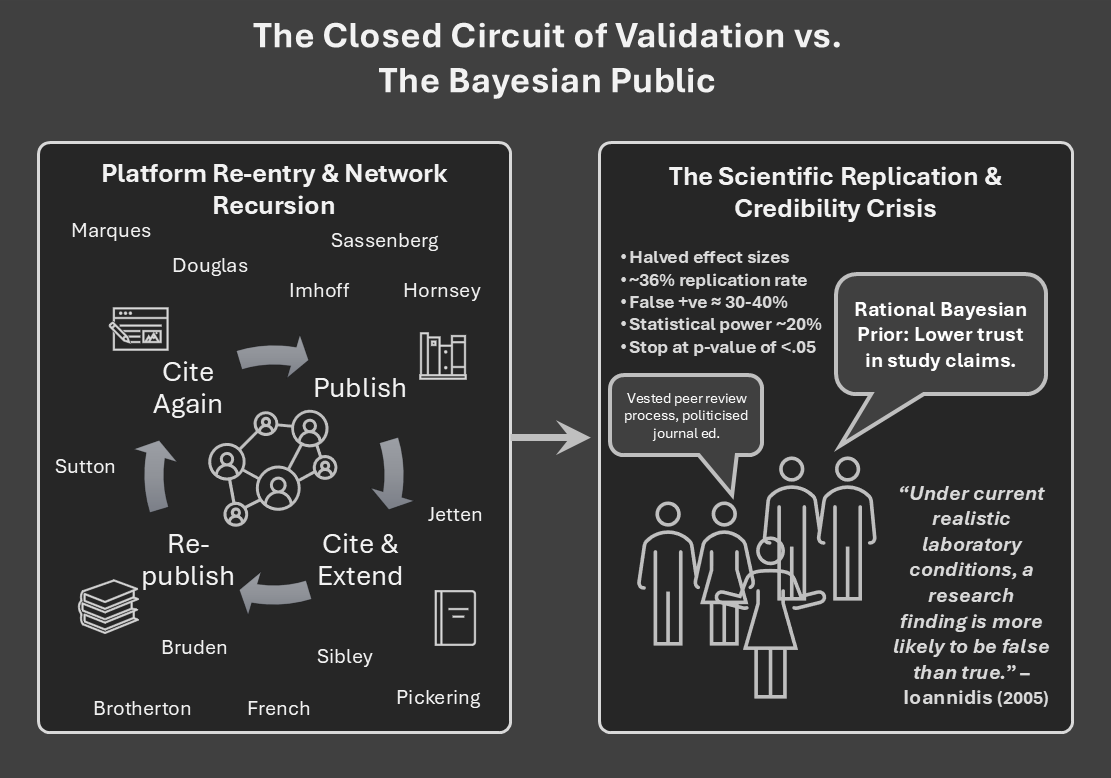

The Closed Network: Consensus-by-Recursion

A small, repeating circle of authors—Imhoff and frequent collaborators (Bruder, Oeberst, Alper), alongside field anchors like Douglas, Hornsey, van Prooijen and Sutton—publish across the same venues (e.g., International Review of Social Psychology; Social Psychological and Personality Science), citing and extending one another’s constructs. As well as in the previous articles in this series, you can see the pattern just by scanning the paper headers and reference trails in the provided corpus: the 2021 IRSP experiment carries the same “conspiracy mentality” scaffolding used elsewhere in the set, and the 2023 perception paper sits in an adjacent, regularly-cited stream. This is not a smoking-gun conspiracy; it’s platform re-entry and network recursion. But in a domain that diagnoses dissent, recursion performs as consensus: each new paper treats the “conspiracy mentality” as settled context, thickening the worldview while rarely facing adversarial audit from out-of-network labs.

The Presumption of Institutional Benignity

That recursion sits on a deeper axiom: major institutions (governmental, corporate, scientific) are the default arbiters of reality; deviation is a property of the subject. The corpus frames trust as the healthy baseline and re-codes distrust as mindset. The analyses make this explicit: “the problem is perception, not conduct,” and the reference lists repeatedly recycle the same in-network authorities. What’s systematically bracketed is a century of counter-evidence that would rationally seed distrust—COINTELPRO’s political policing, Tuskegee’s medical betrayal, the WMD intelligence failure—and, most relevant here, the meta-scientific shock to psychology itself.

The Ioannidis Proof: The Field’s Glaring Blind Spot

CTT papers enthusiastically adopt the rituals of rigor—preregistration, open materials, open data (e.g., the IRSP study’s “open materials and data” banner)—and that’s good practice. But these same papers are almost silent on the meta-scientific critique that should reshape their priors: Ioannidis’s 2005 analysis showing that under common research conditions (low power, analytic flexibility, competitive incentives) “false findings may be the majority or even the vast majority of published research claims.”

This was not merely theoretical. The Reproducibility Project: Psychology attempted direct replications of 100 studies and reported that only ~36% of replication attempts produced significant results (vs 97% of the originals), with replication effect sizes roughly half the originals’. Debate continues about interpretation, but even critics accepted that the base rate of reliable effects is markedly lower than the published record suggests. The upshot is clear: the base rate of false positives in social psychology is elevated enough that a rational public would weight official claims with scepticism.

That’s the Ioannidis Proof for this context: if your home discipline sits on a fragile empirical base, citizens lowering their prior on your assertions is Bayesian hygiene, not pathology. Yet the CTT literature doesn’t model that prior. It polices public trust with prereg badges while leaving the base-rate problem unmodeled in the very studies that diagnose distrust. (Meanwhile, the field’s jurisdiction expands—see “Don’t trust anybody: Conspiracy mentality and the detection of facial trustworthiness cues”—from beliefs into perception, without a parallel reflexive audit of its own knowledge stability.)

The Ultimate Irony

The paradigm that pathologises a sceptical heuristic is built inside a field that publicly confronted replication failure. Ioannidis’s logic—formalised for biomedicine, widely applied across sciences—predicts exactly what a wary public now does: discount single-study claims, especially where incentives and flexibility are high. The CTT frame treats that update as a mindset to be corrected, not as a signal to reweight its own evidentiary claims.

The Unasked Question

The corpus never seriously entertains it:

What if “conspiracy mentality” is, in part, a rational heuristic in an environment where the literature is often unreliable and entangled with institutional incentives?

Even when scope widens—into perceptual domains—the move is jurisdictional (belief → perception) rather than reflexive (belief → our own error bars).

Transparency as Ritual, Not Reckoning

Preregistration and open materials are valuable. They can also perform as authority cues when readers aren’t shown what would actually change minds: error rates, adversarial replications, out-of-network tests designed to falsify the trait-first frame. The soft closure is the problem—self-verification loops and platform re-entry that simulate consensus while the base-rate question remains offstage. None of this implies fraud; these are structural incentives Ioannidis warned about.

The Real Fracture

If psychology’s reliable-effect base rate is closer to the replication estimates than to the published 97% significance veneer, then public scepticism isn’t a disease vector; it’s a reasonable prior. The CTT frame has no place to put that update. It is designed to manage sceptical minds, not to audit the institutions—and the science—producing the claims in the first place.

Real-World Blindness - When the Map Obscures the Territory

(Extending the Ioannidis theme to practical consequences)

The CTT paradigm prides itself on methodological neatness. But its clean lab designs, narrow constructs, and institutional priors create a widening gap with the messy world we actually live in. The result is a research program that speaks confidently about “conspiracy belief” while missing the dynamics of conspiracy practice—state, corporate, and hybrid—now routine in twenty-first-century governance.

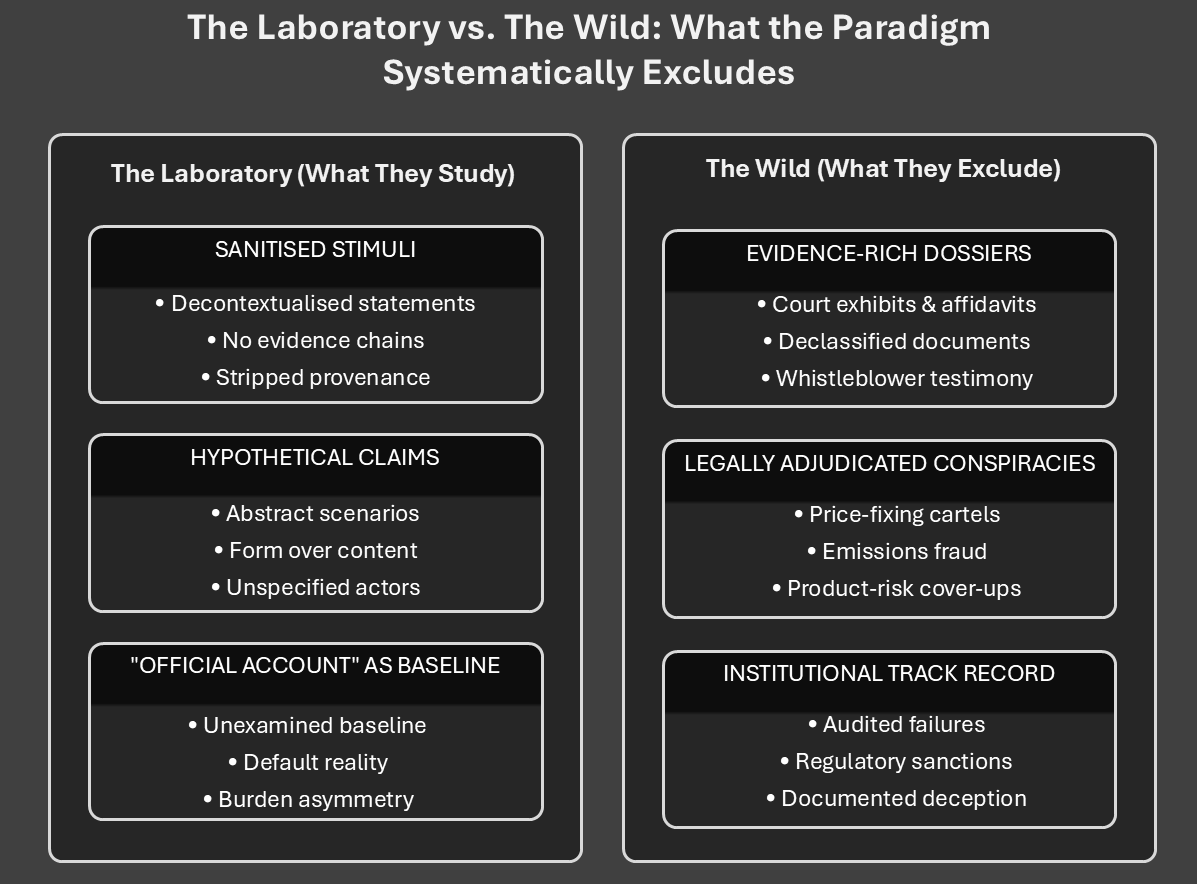

The laboratory vs. the wild

In the lab, participants are shown sanitised stimuli—decontextualised, pre-approved “conspiracy theories” stripped of provenance, evidence chains, or incentive structures. A statement like “secret groups control world events” is scored the same whether the reader is thinking of a comic-book cabal or declassified programs with paper trails. Meanwhile, in the wild, sceptics marshal affidavits, court exhibits, whistleblower documents, audit trails, and congressional reports. By design, the lab excludes those evidentiary scaffolds, then concludes: “belief doesn’t respond to information.” Of course it doesn’t—because the information people actually use was never admitted.

That exclusion produces the circular claim: people believe without evidence, because our studies removed the evidence they cite. It’s a map that deletes the terrain and then declares the terrain irrelevant.

The trust-metric paradox

Psychological scrutiny is applied asymmetrically. Institutional trust is treated as a healthy baseline; distrust is a diagnostic deviation. The paradox is brutal: as more evidence accumulates of institutional failure, misreporting, or capture, the field intensifies diagnosis of the people who notice. When large-scale failures (from war intelligence to mass surveillance to defective products) enter public memory, a rational trust calculus adjusts. The diagnostic frame doesn’t: it keeps reading the updated prior as pathology.

The corporate conspiracy blindspot

There’s a gulf between hypothetical conspiracies (the lab’s staple) and legally adjudicated conspiracies (the courtroom’s staple): price-fixing cartels, emissions fraud, market manipulation, product-risk cover-ups. Major corporations are indicted, settle, or stipulate facts under oath. Yet the psychological construct “conspiracy mentality” rarely distinguishes between a belief about a documented corporate conspiracy and a belief about a fanciful one. The legal reality that conspiracy is a prosecutable crime disappears into a one-size-fits-all mindset score.

The intelligence failure

History is treated as thought experiment rather than precedent. From the Cold War to the present, covert operations, surveillance overreach, disinformation, and domestic political policing leave an archival footprint. The public knows this. CTT designs rarely operationalise these precedents as covariates. Layer on the expert credibility crisis—replication failures in psychology, model misses in economics, sweeping policy reversals in public health—and you get a picture in which “conspiracy mentality” often looks like Bayesian updating under uncertainty, not a malfunctioning detector.

The methodological catch-22

Open science rituals (preregistration, shared code) are good; they’re also insufficient. Ioannidis’ core warning is about design scope and base rates: if you measure the wrong thing cleanly, you still infer the wrong thing. CTT studies are rigorous at measuring predisposition while systematically excluding the most relevant covariates:

- Institutional track record (audited failures, sanctions, consent decrees)

- Evidence strength (document type, corroboration level, adversarial replication)

- Incentive gradients (profit/regulatory exposure, political timing)

A self-referential, high-recursion citation network then amplifies those narrow findings, reading repetition as validation—common in tight subfields, but brittle when out-of-network audits are scarce. That’s not fraud; it’s how a degenerating research programme behaves—protecting core assumptions against the friction of reality.

Where the field contradicts itself (and why it matters)

Even within the corpus, we saw the functional reading of conspiracy claims in corrupt settings: “alarm signals” and a “wake-up call.” That necessarily concedes content can matter. Set that next to the earlier closure cue—“no mechanistic… effect” and “predisposition… the only predictor”—and you have a live contradiction: one thread treats CTs as adaptive vigilance when corruption is high; the other treats content as inert, always. The theory papered over the gap with a context valve; the world won’t.

Design fixes (so the map can see the terrain)

If the aim is understanding—not governance by diagnosis—here’s what a reality-competent design demands:

- Sanitised vs. evidence-laden split. Run paired conditions: (a) abstract statements; (b) evidence-rich dossiers (documents, timestamps, sanctions history).

- Documented vs. hypothetical split. Include legally adjudicated conspiracies (with court records) and compare to hypothetical claims.

- Content × predisposition tests. Pre-register interactions between evidence strength (independently audited) and predisposition, with falsifiable thresholds where content must move belief if the model is to survive.

- Institutional record covariates. Add country/sector indices for corruption findings, regulatory enforcement intensity, retraction/replication rates, consent decrees—then test switch-points where context overtakes trait.

- Out-of-network replications. Require orthogonal labs to pit a trait-first model against rational-updating models using the same dossiers.

Post-hoc concession as control (who gets to define “real”?)

There’s a quiet institutional bias built into the way “real” conspiracies enter the CTT frame: only after official adjudication, declassification, or elite media consensus do they count as legitimate examples. Before that threshold, citizen suspicion is scored as mentality. After the state (or a court, or a prestige outlet) certifies the facts, the same suspicion is retrofitted as “understandable”—but the epistemic credit accrues to the institution that finally acknowledged it, not to the public that detected it. This post-hoc acknowledgement functions as a reality gate: institutions decide when evidence “exists,” thereby preserving the diagnostic lens in the interim and defining the timing and terms of concession when the facts become undeniable. This produces an asymmetric risk, where the public pays a stigma tax for early detection; institutions pay nothing for late admission. In practice, that means the framework penalises timely vigilance and rewards belated validation.

The real-world cost

This blindness isn’t just academic. By pathologising legitimate scepticism, the CTT paradigm:

- Provides cover for institutions to avoid accountability (“the problem is the public”)

- Misdiagnoses symptoms as causes, blaming dissent for instability produced by institutional performance

- Justifies dismissal of valid concerns about concentrated power with a diagnostic label

- Erodes democratic accountability by medicalising political disagreement.

And so the ultimate irony holds: a field devoted to identifying false beliefs has built an apparatus that reliably generates false negatives about institutional untrustworthiness—while producing false positives about public pathology. Until the map admits the mountain ranges plainly visible on the ground, it will keep telling travellers they’re lost for noticing the terrain.

The Unstable Core

The loop, compressed shows:

Build a trait → prove content is irrelevant → absorb contradictory context → jump from beliefs to perception.

This scaffold powers the entire programme. Its fractures show where the structure can’t carry the weight of reality.

The live fracture points (with brittleness ratings) are:

- Trait Primacy vs. Context Rationality — High brittleness

The data itself frames CTs as “alarm signals… a ‘wake-up call’” in corrupt settings. That’s a functional reading of content—yet the core doctrine insists content is inert and trait explains everything. The model cannot hold both without tearing. - Method-as-Mandate vs. Discovery — High

The CMQ presupposes a general mindset; the LPA then declares “uniform patterns” as proof of it. The tool bakes in the ontology, then the method validates it. This is a circular proof, a hinge with no independent bearing. - Content-Null Seal vs. Evidence in the Wild — High

The lab finding of “no mechanistic… effect” collides with the evidentiary dossiers used in the real world (documents, court exhibits, audits). The paradigm’s map deletes the terrain, then declares the terrain irrelevant. - Benignity Prior vs. Ioannidis Base Rates — High

A field with a demonstrated high false-positive rate and halved replication effects polices the public’s “irrational” priors. A rational Bayesian update—discounting official claims—directly contradicts the doctrine. Institutional trust as a baseline cannot survive its own error bars. - Jurisdiction Hop vs. Missing Bridge — Moderate–High

The leap from belief to perception (e.g., “Don’t trust anybody”) is made without a preregistered, falsifiable causal bridge. Without a mechanism, this looks less like explanation and more like jurisdictional expansion. - Transparency Ritual vs. Reflexive Audit — Moderate

Preregistration and open materials perform rigor, yet the model systematically omits institutional track records and evidence strength as covariates. This is the clean measurement of the wrong thing.

Questions:

- Where is the switch-point? At what level of corruption does context overtake trait? This must be pre-registered.

- What actually moves belief? Run content × predisposition tests using independently audited evidence strength.

- Can the loop survive? Submit it to out-of-network labs and model competition against rational-updating baselines.

- What is the bridge? Specify a falsifiable mechanism for the belief → perception leap.

- Who defines “real”? Decouple validity from post-hoc institutional admission; track the epistemic lag between public claims and official concessions.

Last Words

This analysis offers no policy prescription. No catharsis. The CTT governance thesis remains unstated by design, yet is now unavoidable: the programme is architected to diagnose citizens more than it audits institutions.

That is the fundamental fracture. It is structural, not stylistic.

Imhoff co-authored papers used in the analysis:

· Frenken, M., & Imhoff, R. (2021). A uniform conspiracy mindset or differentiated reactions to specific conspiracy beliefs? Evidence from Latent Profile Analyses. International Review of Social Psychology, 34(1):27, 1–15. [Open Access Article] [Open materials and data]

· Meuer, M., Oeberst, A., Imhoff, R. (2021). Believe It or Not – No support for an effect of providing explanatory or threat-related information on conspiracy theories’ credibility. International Review of Social Psychology, 34(1):26, 1-13. [Open Access Article] [Open materials and data]

· Rudert, S., Gleibs, I. H., Gollwitzer, M., Häfner, M., Hajek, K. V., Harth, N., Häusser, J. A., Imhoff, R., & Schneider, D. (2021). Us and the virus: Understanding the COVID-19 pandemic through a social psychological lens. European Psychologist, 26, 259-271.

· Frenken, M., & Imhoff, R. (2022). Malevolent intentions and secret coordination. Dissecting cognitive processes in conspiracy beliefs via diffusion modeling. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 103, Article 104383. [Preprint] [Open materials and data]

· Frenken, M., & Imhoff, R. (2023). Don’t trust anybody: Conspiracy mentality and the detection of facial trustworthiness cues. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 37, 256-265. [Open Access Article] [Open materials and data]

· Alper, S., & Imhoff, R. (2023). Suspecting Foul Play When It Is Objectively There: The Association of Political Orientation with General and Partisan Conspiracy Beliefs as a Function of Corruption Levels. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 14, 610–620. [Open Access Article]

Published via Journeys by the Styx.

Mindwars: Exposing the engineers of thought and consent.

—

Author’s Note

Produced using the Geopolitika analysis system—an integrated framework for structural interrogation, elite systems mapping, and narrative deconstruction. Assistance from Deepseek for composition and editing.