Overlords Addendum1: The Harmonisation Engine’s Original Code-Writers

How seven ideological guilds wrote the source code for a global governance system that runs on credentials, not consent.

In the Overlords arc, each instalment has stripped away a layer of the theatrical state to expose the operational core — rule not as rhetoric but as protocol. Part 7 marked the moment when the system’s prototypes, mapped in earlier chapters, were no longer confined to their originating regimes. The UAE’s runtime governance, Singapore’s micromodel, and China’s permissioned prosperity framework appeared not as exotic outliers but as nodes in a single, interoperable control lattice. What emerged was a live stack: modular, trans-jurisdictional, and indifferent to political branding.

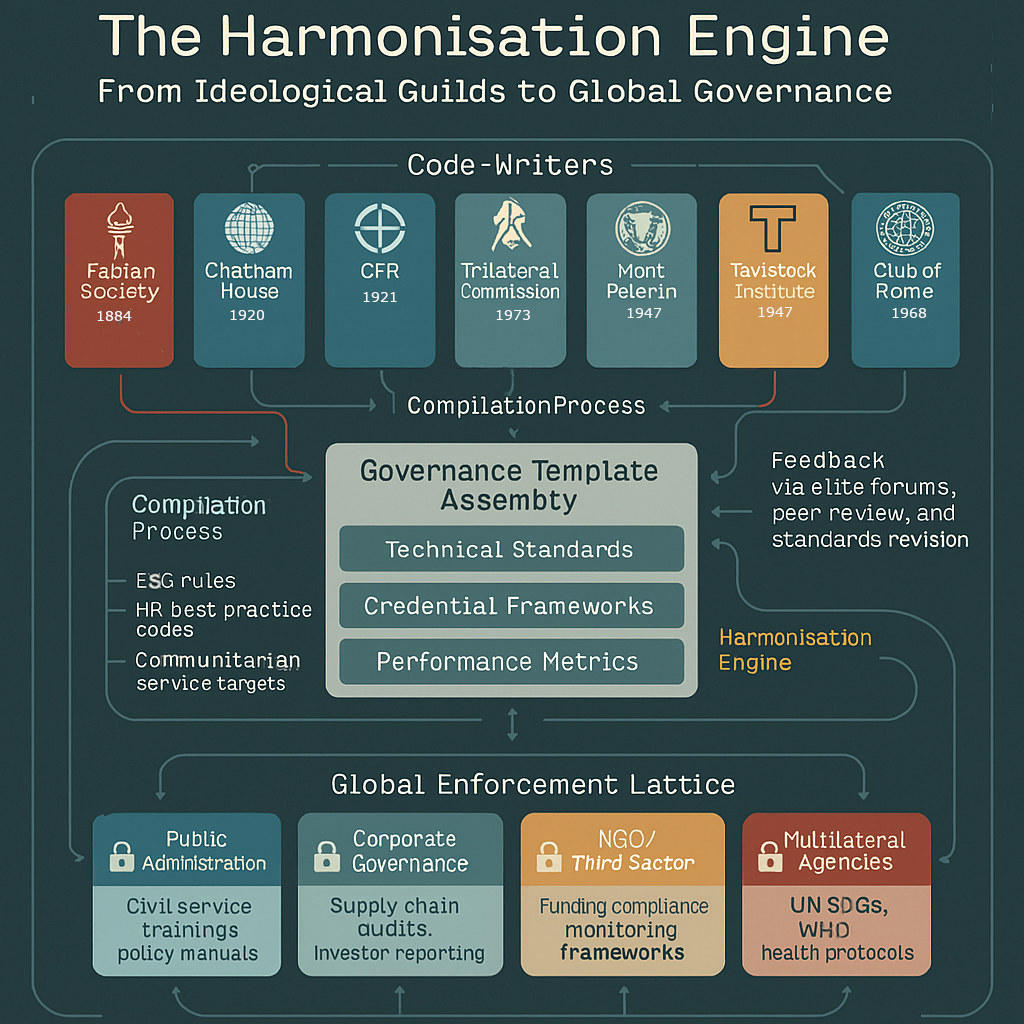

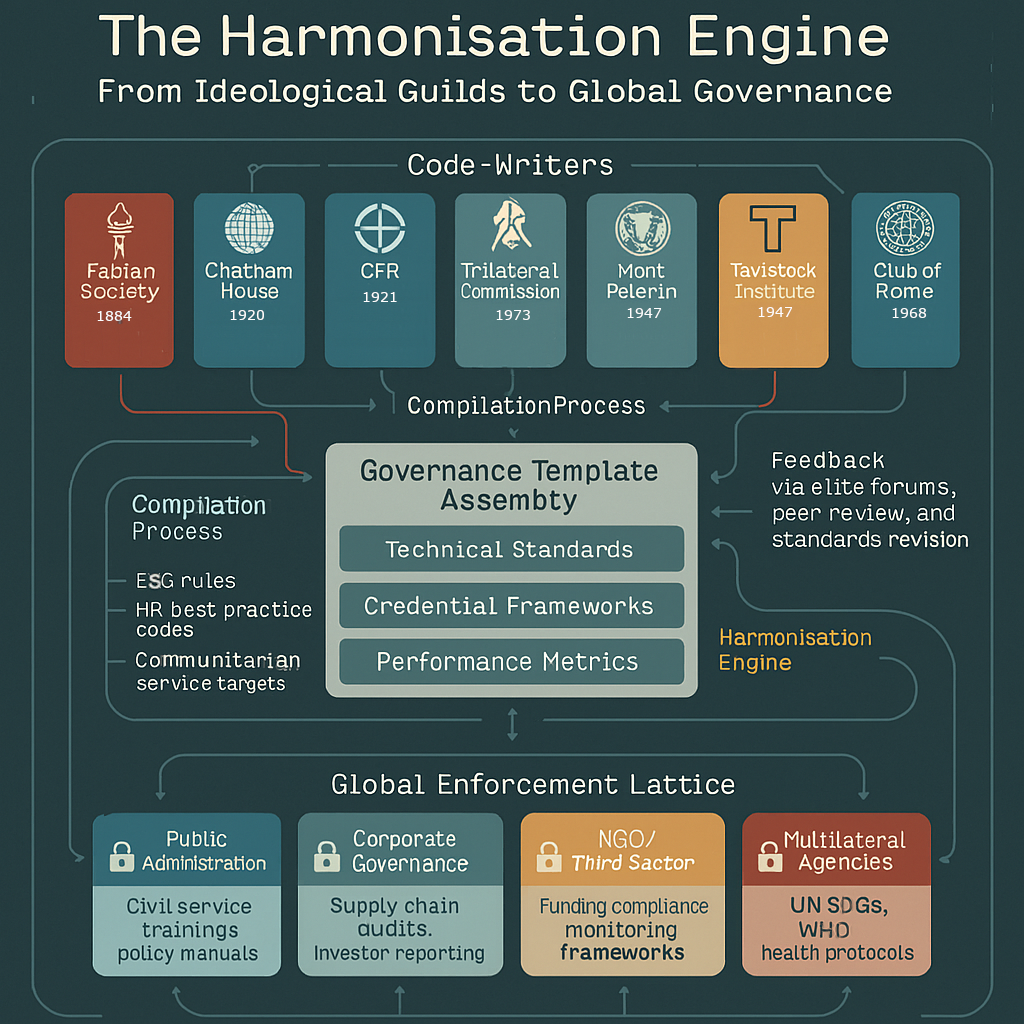

This inquiry sits directly on that seam. Where Part 7 identified the harmonisation engine—the institutional layer that synchronises health, finance, surveillance, and sustainability into a single administrative runtime—this article traces its upstream authors. The Fabian Society, Chatham House, the Council on Foreign Relations, the Trilateral Commission, the Mont Pelerin Society, Tavistock, and the Club of Rome are not peripheral to this lattice; they are its code-writers. Long before the digital layer, they were designing governance templates that could be skinned in any ideology yet run on the same architecture.

Modern governance is shaped less by parliaments than by elite networks — think tanks, policy institutes, and transnational commissions — that compile policy logic into ready-made templates. These templates are then embedded in regulations, certifications, and performance metrics, making compliance a condition for participation in commerce, public service, or institutional funding. Because these frameworks are framed as technical or expert-driven, they bypass electoral volatility and democratic debate, installing rules through credentialed enforcement rather than public consent.

The point is not clandestine conspiracy — their meetings, publications, and membership lists are often public — but structural function. For decades, these bodies have been compilers of control logic, seeding communitarian duty, neoliberal orthodoxy, behavioural compliance, and planetary sustainability into the multilateral and national systems Part 7 mapped as enforcement points. They are the historical firmware of the convergence stack, supplying the source code the harmonisation engine now runs.

This also sets the stage for Part 8, where the focus shifts from the architecture to its operators — a permanent managerial class that acts as the living interface between elite forums and the enforcement stack. The system is not by any single ideology; it is designed to metabolise any that can carry its control logic.

Lead: From Think Tank to Protocol

The public image of these organisations is crafted around the language of debate, research, and policy advice — forums where learned elites exchange ideas for the betterment of governance. In practice, they function less as debating societies and more as upstream compilers of governance logic. Their role is to draft the schema before the political process begins, to define the boundaries of legitimate policy long before legislation, regulation, or public consultation are invoked.

From the Fabian salons of late 19th century Britain to the transatlantic policy circles of the post–Second World War order, the continuity is structural. Each generation’s flagship bodies inherited the same core function: to translate elite preferences into frameworks that could be embedded in the machinery of state and multilateral institutions. The outputs differ in ideological skin—socialist gradualism, free-market neoliberalism, communitarian behavioural management, planetary sustainability—but these are variations in branding, not in architecture. Each path routes to the same endpoint: a technocratic system where authority flows from credentialed compliance with pre-agreed metrics, rather than from direct democratic mandate. These organisations function as upstream narrative locking devices—constructing pre-consensus environments through controlled saturation of credentialed outputs.

The result is functional convergence. Whether advancing collective duty, market discipline, population conditioning, or environmental stewardship, the deliverable is a governance template that can be slotted into any jurisdiction’s administrative core. This template comes pre-loaded with standards, data requirements, and performance indicators—the very modules the Part 7 harmonisation engine now runs at global scale. In this light, the distinction between ideological camps dissolves. What matters is not the rhetorical banner under which the code is written, but the fact that it compiles into interoperable protocols for rule without public contest.

These seven organisations examined in this article merit closer examination because they form a representative cross-section of the code-writing layer itself. Each occupies a distinct position in the historical relay — from the Fabian Society’s slow-drip institutional capture to Mont Pelerin’s market-liberal discipline, from Tavistock’s behavioural formatting to the Club of Rome’s planetary constraint models — yet all feed into the same policy metabolism. By tracking them in sequence, it becomes possible to see not just their individual outputs but the shared engineering principles: closed-door drafting, credential-mediated dissemination, and standards-based enforcement. Together they illustrate how apparently rival traditions supply interchangeable modules to the same administrative runtime, allowing the harmonisation engine to metabolise socialism, neoliberalism, environmentalism, or behavioural science with equal efficiency.

1. The Fabian Society — Communitarianism as Policy Skin

Founded in 1884, the Fabian Society emerged in an era when socialism was largely associated with revolutionary upheaval. Its founders—Sidney Webb, George Bernard Shaw, Graham Wallas, Annie Besant, Edward R. Pease, Frank Podmore, and Percival Ashley Chubb—rejected rupture in favour of a long game: elite-led, incremental reform implemented through the existing machinery of state. The chosen metaphor, drawn from the Roman general Fabius Maximus, was deliberate: slow encirclement rather than frontal assault. This approach positioned the Society not as a mass movement but as an incubator for policy logic, to be fed downstream into parties, ministries, and bureaucracies.

The organisation’s own iconography betrayed this tactical posture. For decades, the Fabian coat of arms depicted a wolf in sheep’s clothing—an emblem of strategic disguise in pursuit of transformation. Officially retired in later years, it encapsulated the Society’s core method: advancing systemic change under the cover of familiar forms, embedding systemic transformations within existing administrative forms to avoid public disruption signals.

The Society’s most enduring vector was its integration with the Labour Party from the early 20th century onward. Fabians supplied ministers, civil servants, and advisers—among them Clement Attlee, Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, James Callaghan, and G. D. H. Cole—who carried its programmatic instincts into legislation and administrative practice. International figures such as Jawaharlal Nehru also passed through its executive committee, reflecting its reach beyond Britain. Over decades, this produced a reliable pipeline: ideas formulated in Fabian pamphlets and discussion circles would reappear as government white papers, regulatory frameworks, or statutory mandates, often stripped of any visible link to their origin.

Beyond communitarian planning, the Society operates as a behavioural norm encoding engine—embedding performance-metric governance beneath the moral texture of equity, preconditioning the public for synthetic consent via managerial rationalism. Its signature contribution to governance was the normalisation of technocratic planning within an electoral system. Fabians recast centralised economic and social management as the natural expression of democratic will, framing it in the language of fairness, social justice, and collective responsibility. Under this communitarian skin, policy became a matter of balancing individual liberties against perceived collective needs — a balance defined and measured by professional planners, not by direct public mandate.

Operationally, this translated into the soft erosion of parliamentary sovereignty. narratives provided the moral cover to embed performance metrics, service eligibility criteria, and administrative targets into public services. The more functions were defined in terms of measurable outputs, the more authority shifted from elected representatives to credentialed administrators. Contemporary political figures sustain the Fabian lineage the Society’s vice-presidents—including Nick Butler, Lord Dubs, Kate Green, Baroness Hayter, Dame Margaret Hodge, Lord Kinnock, Sadiq Khan, Seema Malhotra, Christine Megson, Baroness Thornton, and Giles Wright—maintain its place in the political bloodstream. Keir Starmer, current UK Prime Minister, served on the Society’s executive committee and has contributed to its policy work, carrying forward the tradition of embedding communitarian and technocratic frameworks within mainstream electoral politics. Notably, Starmer also has previous linkages to the Trilateral Commission (see below). The integration of communitarian metrics within electoral politics operates as a closure mechanism—translating procedural visibility into scripted legitimacy, decoupled from direct public authorship.

By design, the Fabian method presents this transfer not as a diminishment of democracy, but as its efficient fulfilment — a framing that would prove central to the later harmonisation engine mapped in Part 7.

2. Chatham House — Closed-Door Convergence

Founded in 1920 in the aftermath of World War I, Chatham House was conceived as the British counterpart to the Council on Foreign Relations—both descending from the Rhodes–Milner Group’s Round Table design for sustaining imperial reach through intellectual and administrative proxies. From inception, its purpose was not to arbitrate public debate but to concentrate elite agreement on foreign policy, trade, and governance norms, then feed this alignment into state and multilateral machinery.

Its structure is that of a controlled forum: invite-only, shielded from public scrutiny, operating under the eponymous Chatham House Rule to protect attribution while preserving influence. This insulation allows it to convert informal consensus into formal frameworks without exposing the underlying authorship. The process is recursive — upstream strategic preferences are formatted into analysis, released as reports or policy briefs, and absorbed by ministries, supranational bodies, and media channels as if they originated within those institutions.

Chatham House exemplifies the governance simulation system, where staged pluralism disguises upstream consensus as democratic deliberation. Under the Chatham House Rule, its outputs function as sanitised templates—primed for supranational uptake while masking origin authorship.

The function is not to generate options but to preconfigure the field of permissible policy. In the NATO case study analysed in Geopolitika, Chatham House did not simply contribute to debate on Europe’s role; it staged a pre-summit narrative that cast militarisation and deeper integration as inevitable responses to a manufactured triad of threats—Russian aggression, European disunity, and American withdrawal. The document simulated pluralism through a cast of former generals, ministers, and policy figures, each assigned to voice a motif within a pre-sequenced script. The effect was to mask a single authorship voice behind institutional avatars, making consensus appear organic. This simulation of contested terrain conceals upstream authorship through narrative sequencing. By staging dissent within pre-approved boundaries, Chatham activates reversal logic—turning debate into reinforcement.

This pipeline—closed-door drafting, curated polyphony, public release as analysis—produces policy templates that appear state-authored but are in fact preformatted in the Chatham network. Whether in defence posture, trade architecture, or governance standards, Chatham House functions as a codifier node in the harmonisation engine mapped in Part 7: shaping interoperability conditions and political obligations in advance, so that when governments act, they are ratifying a framework already written. Policy is not debated, but revealed as inevitable. The future is framed as constraint rather than choice, with alternatives erased via strategic foresight converted into default logic.

3. Council on Foreign Relations — US Foreign Policy Compiler

The Council on Foreign Relations was founded in 1921 by a coalition of bankers, industrialists, senior diplomats and academics—many of them veterans of the U.S. delegation to the Paris Peace Conference and closely tied to the Morgan banking network. It emerged as the American counterpart to Britain’s Royal Institute of International Affairs (Chatham House), inheriting the closed-door policy circle model developed by the British Round Table movement. From inception, CFR was designed as a permanent forum where finance, defence and foreign policy elites could align long-term strategy—embedding imperial management techniques into an ostensibly national institution that would guide U.S. global engagement beyond the reach of electoral disruption.

This alignment materialises in long‑term strategic planning, disguised as neutral expertise. For example, as discussed in a previous Geopolitika article, CFR’s Special Initiative on Securing Ukraine’s Future—including the report—does more than assess damage or propose aid. It crafts a predesigned roadmap: repatriation of labour, signalling for private capital, institutional reform and financial stabilisation are structured as inevitable, consensus‑driven policy outcomes. Public events and policy forums—such as symposia—perforate the appearance of open debate while delivering preformatted templates that governments then ratify.

Even proposals appear state‑authored but emerge fully formed from CFR’s drafting process. For instance, CFR briefs on long‑term recovery, economic incentives, and population return are treated as independent state plans yet bear the imprint of CFR’s upstream design.

CFR operates as a node within the perception management regime, functioning as a narrative seeding organ where elite policy consensus is framed as neutral analysis. Its role is to convert strategic foresight into epistemic inevitability, later diffused via policy proxies and credentialed media loops. Its influence withstands partisan rotation. Whereas administrations shift, CFR retains its role in codifying post-conflict reconstruction as technical necessity—not political option. By framing Ukraine’s rebuilding as not just desirable, but logically preordained, CFR compresses creative space. Its frameworks are absorbed, then naturalised by state actors.

In sum, CFR’s role is not advisory in the nominal sense—it is the compiler of U.S. foreign-policy readiness. Through institutional continuity, expert consensus rituals, and preformatted policy blueprints, it pre-engineers geopolitical outcomes, insulating them from both democracy and disruption.

4. Trilateral Commission — Interdependence at Geopolitical Scale

The Trilateral Commission was established in 1973 by David Rockefeller — then chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations and chief of Chase Manhattan Bank — together with political scientist Zbigniew Brzezinski, later U.S. national security adviser. Its founding membership drew from the political, financial and academic elite across North America, Western Europe and Japan, with the first North American chairman, Gerard C. Smith (1973–77), followed by Rockefeller himself, then Paul A. Volcker, all exemplars of the trans-Atlantic technocratic class. The Commission functions as a backend compiler—translating elite cohesion into state-readable compliance modules. Its outputs serve as scaffolding for interoperable policy enactment across jurisdictional shells.

Branded around the concept of the Commission’s doctrine operated as a macro-level stakeholder model, reframing sovereignty through the claimed necessity of coordinated economic management across the three poles, and reducing the space for unilateral national policy. Its operational design — elite summits, working groups, and closed-door reports—channelled consensus directly into global institutions such as the G7, IMF and WTO, ensuring that Commission blueprints were implemented as government policy rather than left to academic debate.

The Trilateral Commission functions as a coordination relay node—calibrating synchrony between North American, European, and Asian elites. It refines narrative velocity and motif cohesion across regions, forming a backbone of policy pre-alignment infrastructure that primes multilateral organs for seamless enactment. Across decades, the roster has carried figures like Madeleine Albright, Graham Allison, and other long-standing Washington insiders, alongside European and Asian counterparts with parallel reach into finance, diplomacy and corporate governance. Current chairs continue the tri-region architecture: Meghan O’Sullivan for North America, Axel A. Weber for Europe, and Takeshi Niinami for Asia Pacific, with deputies such as Carl Bildt and Barry Desker, and executive directors Richard Fontaine and Paolo Magri. These leaders — like Weber, who has cycled through the Deutsche Bundesbank, ECB, BIS, IMF and G20 forums, or Desker, who ran Singapore’s premier strategic think tank — exemplify the Commission’s revolving-door function. Membership has extended into current political leadership, notably Keir Starmer, who joined while serving on the UK’s opposition front bench and appeared at Commission events alongside former MI5 and GCHQ directors. Such overlaps illustrate the Commission’s enduring role as a convergence node where political, intelligence, financial and corporate spheres integrate governance logic. In every phase, its influence rests not on public advocacy but on recruiting, circulating and embedding personnel whose coordinated outlook ensures remains the unspoken operating code of statecraft.

Beyond personnel circulation, the Commission’s impact is traceable in policy sequences. Position papers on trade liberalisation, monetary coordination, and energy security have prefigured G7 communiqués and WTO negotiation lines. Its reports on managing emerging economies’ integration into global markets appeared in parallel with IMF conditionality frameworks, while its early advocacy of harmonised regulatory standards anticipated the architecture of the OECD and Basel accords. Even climate and technology governance initiatives have borne the Commission’s imprint, with rhetoric now embedded in EU strategic autonomy policy and US–Japan technology alliances. Such outputs, framed as neutral expertise, function as compiled governance code — shaping agendas before public debate and locking in strategic trajectories that serve the very networks from which the Commission draws its members.

5. Mont Pelerin Society — Neoliberal Parallel to Fabian Gradualism

The Mont Pelerin Society was established in 1947 under the leadership of Friedrich Hayek, bringing together a circle of economists, historians, and journalists committed to resisting post-war collectivism and embedding market orthodoxy into Western governance. Its founding members included Ludwig von Mises, Wilhelm Röpke, Lionel Robbins, and Milton Friedman — figures tied to the Austrian School’s rejection of central planning and advocacy for spontaneous order. From the outset, its operational method mirrored Fabian gradualism: secluded retreats for elite participants, circulation of policy papers, and the spawning of think tanks designed to reformat national policy from the academic apex downward.

Mont Pelerin serves as the doctrinal forge for the neoliberal mask of legitimacy, producing market absolutist logic in service of asset concentration and regulatory incapacitation. Functionally, it acts within the epistemic shell infrastructure—dressing elite consolidation as economic rationality. While grounded in Austrian economics, Mont Pelerin became the institutionalised and elite-integrated branch of that tradition. It adapted Hayek’s and Mises’s theories into forms palatable to post-war governments, favouring incremental reforms over revolutionary economic rupture. This strategic moderation created distance from purist Austrians like Murray Rothbard, who never joined the Society and accused it of diluting principles by accepting Keynesian compromises and sustaining welfare-state scaffolding in exchange for influence.

Ron Paul’s libertarian movement drew on the same Austrian intellectual heritage — especially in its anti–Federal Reserve stance and commitment to sound money — but operated outside the think tank–university pipeline Mont Pelerin cultivated. While Paul found selective allies among Mont Pelerin members on monetary policy, his broader non-interventionist and sovereignty-first agenda ran counter to the Society’s alignment with global economic integration through institutions like the IMF, World Bank, and WTO.

Prominent members over time have included George Stigler, James Buchanan, and Gary Becker, as well as political figures such as Margaret Thatcher, who directly credited Mont Pelerin’s intellectual network for shaping her market reforms. In effect, the Society served as the neoliberal parallel to Fabian gradualism — both using elite networks to set governance norms, both masking structural similarity under opposing ideological brands. Where Fabians embedded communitarian control inside democratic systems, Mont Pelerin embedded market discipline inside global governance, each functioning as a standard-setting compiler for the respective code paths of technocratic rule. Mont Pelerin’s outputs are not theories but enforcement blueprints routed through trade treaties, credit frameworks, and state reform conditionalities.

Margaret Thatcher drew directly from the Society’s network and canon: Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty was famously kept in her ministerial briefcase, and several of her economic advisers — including Alan Walters and Patrick Minford — were either members or close affiliates of Mont Pelerin–linked think tanks like the Institute of Economic Affairs and the Centre for Policy Studies. The structural reforms associated with Thatcherism — privatisation, deregulation, union curtailment, monetarist policy discipline — were policy manifestations of the neoliberal orthodoxy the Society had been standardising since the late 1940s.

Functionally, Thatcherism translated the Mont Pelerin framework from academic and conference circuits into the command stack of a G7 state, demonstrating that the Society’s long-game of elite incubation could reshape national economic governance without overt revolutionary rupture — mirroring Fabian gradualism’s method, but with inverse ideological branding.

6. Tavistock Institute & Behavioural Science Bodies — Conditioning the Population Layer

The Tavistock Institute emerged in 1947 from the Tavistock Clinic’s wartime role in British Army psychiatry, where psychoanalytic techniques were applied to combat stress and personnel selection. Under leaders such as Elliott Jaques, Tommy Wilson, and Eric Trist—with Rockefeller and later Ford Foundation backing—it evolved into a behavioural laboratory, exporting its systems psychodynamics, socio-technical theory, and group-relations methods from clinical settings into corporate, state, and educational frameworks.

Initially framed as humanising workplace systems through participative design, these tools were repurposed into compliance-enhancing protocols across HR, media, public health, and education—shaping attitudes while presenting engineered change as cultural drift. Corporate projects for Unilever, Shell, and the National Coal Board, early consumer-behaviour studies, and policy-oriented work in child welfare via attachment theory all blurred research, consultancy, and governance.

This trajectory reached a public inflection point with the 1989 creation of the Gender Identity Development Service (GIDS) under the Tavistock and Portman NHS Foundation Trust, which grew from 72 referrals in 2009 to over 1,800 by 2016–17. Whistleblower David Bell’s 2018 warnings of unsafe practices, the Bell v Tavistock litigation, and the Cass Review’s conclusion that the service was led NHS England to close it in 2022, with operations ending in March 2024.

The scandal exposed the fragility of Tavistock’s behavioural-engineering ethos: a system built for shaping populations found its operational logic discredited when detached from evidential rigour. Across its lifespan, Tavistock charted a disciplined path from military psychiatry to institutional norm-setting, embedding as training modules, organisational diagnostics, and therapeutic frameworks that quietly aligned personal dispositions with policy objectives.

During the COVID-19 period, Tavistock’s influence was indirect but infrastructural, operating through alumni, licensed methodologies, and the normalisation of behavioural science in governance. Its wartime-derived frameworks—audience segmentation, morale management, and attitude change—were visible in UK behavioural-science units such as the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT), whose campaigns framed compliance with the governments lockdown, mask wearing and social distancing measures.

Within the NHS, Tavistock-trained approaches informed resilience programmes and organisational adaptation strategies to sustain staff cohesion under shifting protocols. The Institute itself kept a low profile, but the pandemic response reflected its long-standing role in embedding population-conditioning logic inside public health messaging and institutional culture. Tavistock functioned as a vector in the cognitive suppression complex, synthesising psychiatric authority with institutional programming to pre-encode behavioural compliance.

Notably during the pandemic, Marian Brooke Rogers OBE, Professor of Behavioural Science and Security at King’s College London, chaired both the Cabinet Office’s Behavioural Science Expert Group (BSEG) and co‑chaired SAGE’s pandemic SPI‑B subgroup—positioning her at the core of UK behavioural policy-making during COVID‑19. Meanwhile, Professor Susan Michie of UCL chaired the WHO’s Technical Advisory Group on Behavioural Insights and served on SAGE’s SPI‑B as well, applying Tavistock‑derived behaviour‑change frameworks in pandemic messaging and compliance design. At Tavistock itself, CEO Dr Eliat Aram oversaw organisational adaptation and resilience programming—shifting professional training online and designing interventions suited to remote collaboration.

7. Club of Rome — Sustainability as Planetary Governance

The Club of Rome was founded in 1968 by Italian industrialist Aurelio Peccei and Scottish scientist Alexander King as a network of business leaders, scientists, and senior officials, ostensibly to address From the outset, its modelling assumed that population growth was a core destabiliser—positioning humanity itself as the variable to be reduced. This framing established a causal chain: first, posit that there are too many people; second, recast human activity as the root driver of ecological and resource crises; third, identify a pretext capable of justifying transnational control measures. The 1972 Limits to Growth report, produced with MIT’s Systems Dynamics Group, supplied that pretext in the form of environmental constraint, using computer models to project collapse scenarios unless economic and demographic were imposed.

From there, Club of Rome output seeded the policy soil for environmental governance as a sovereignty-bypassing domain. Its systems-analysis logic migrated into the Brundtland Commission’s Our Common Future (1987), the 1992 Earth Summit, and later into the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—each iteration reinforcing the premise that planetary stability required managed contraction of human impact, population, and consumption. The organisation’s alumni and affiliates moved into the UN, World Bank, OECD, and European Commission, ensuring that scenario modelling morphed into binding frameworks. Scarcity forecasting serves not as alert, but as pre-legitimisation of rule—manufactured inevitability anchoring authority to the appearance of necessity. By the 2000s, these ideas were embedded in ESG metrics, carbon markets, and climate-linked financial instruments, transforming environmental targets into programmable compliance obligations.

The Club’s influence lies less in public campaigning than in the quiet conversion of environmental discourse into programmable compliance modules: scenario modelling that becomes baseline assumption; normative targets that become trade, finance, and reporting requirements. In this sense, it parallels the Fabian and Mont Pelerin models—ideological veneer masking a governance compiler—here using ecological necessity as the legitimating frame for centralised, long-horizon control.

The enduring method mirrored other elite networks: pre-format the logic upstream, embed it in multilateral agreements, then operationalise through trade rules, investment codes, and regulatory reporting. In the Club of Rome’s case, ecological necessity served as the legitimating skin for a governance model that treated population control not as a by-product, but as an underlying operational aim. By staging future-scarcity forecasts as moral imperatives, the Club of Rome aligned with the predictive programming arm of perception management regimes.

Convergence: Function over Ideology

These entities wear distinct ideological skins—Fabian socialism, neoliberal market orthodoxy, environmentalism, behavioural science—but their operational code converges. Each functions as an upstream compiler of governance logic, taking informal elite consensus and converting it into technical standards, credential requirements, and performance metrics. This conversion process obscures authorship, presenting the resulting frameworks as neutral, expert-driven, or even inevitable.

They achieve this by designing governance templates in closed-door settings, then seeding them into sectoral whose outputs appear apolitical. A sustainability metric devised in a Club of Rome–linked group is repackaged as an ESG reporting rule, enforced through corporate audit requirements. A Tavistock-derived behavioural framework becomes a mandated HR written into accreditation criteria for public and private sector employers. Fabian communitarian language enters party manifestos, is converted into statutory service targets, and then embedded in compliance audits for local authorities. Mont Pelerin economic doctrine is published in academic policy papers, adopted into international trade rules, and enforced through IMF and WTO conditionalities.

Each of these examples follows the same path: authored in elite forums, legitimised through technical or professional channels, and made binding through credential dependencies. Whether the actor is a multinational, a civil servant, or an NGO, participation requires certified compliance with these prewritten standards—certifications designed, awarded, and policed by the same networks that authored the original frameworks. This alignment ensures that diverse policy fronts feed into a single enforcement architecture, with ideological branding serving only as the point of entry. In each case, the ideological façade is discarded once the template enters the credentialing system—what remains is a standardised enforcement mechanism that treats all domains as interchangeable inputs to the same governance machine.

Once these frameworks enter the regulatory system, they are enforced not by direct political mandate but by credential dependency: a company cannot win a government contract without ESG compliance certification; a civil servant cannot advance without accredited training aligned to approved governance doctrines; an NGO cannot secure funding unless its monitoring and evaluation metrics match those already in circulation. In effect, these bodies create a closed circuit where the same elite networks write the standards, credential the actors, and sit on the review boards—ensuring ideological alignment while maintaining the appearance of pluralism.

The embedding of policy in frameworks that appear apolitical—regulatory language, compliance architectures, certification systems—enables them to bypass electoral volatility and public debate. By placing the mechanics of governance inside technical standards rather than legislative battles, they shift decision-making from parliaments to policy labs, think tanks, and executive agencies. Their frameworks bypass electoral validation through implementation in supranational compliance systems masquerading as democratic continuity. Whether the entry point is gradualist reform, free-market efficiency, planetary sustainability, or evidence-based behavioural management, the functional result is the same: governance without consent mechanisms.

This produces what can be described as a credential-gated noocracy—a form of rule by the in which formal authority is legitimised not by electoral mandate or inheritance, but by demonstrated alignment with sanctioned expertise and harmonised protocols. In this model, participation in governance, access to capital flows, or even basic professional activity is conditional on adherence to a closed-loop credentialing system. The gatekeepers are not elected officials but the institutions that design, award, and police the certifications, metrics, and benchmarks originating in these elite policy networks. The geopolitical export of these logic templates often coincides with debt-leverage enforcement, soft power penetration, or resource-conditional aid schemes

Closing Vector: From Ideological Guilds to Permanent Managerial Class

The entities outlined above operate less as competing ideological movements than as guilds—each with its own branding, initiation rites, and internal myths—but all feeding into a shared operational architecture. Their members circulate across think tanks, regulatory agencies, corporate boards, and multilateral bodies, carrying with them not fixed doctrines but a portable skill set: translating elite consensus into enforceable frameworks. This mobility produces an operator class that functions as a living interface between closed-door policy forums and the enforcement stacks that control capital, regulation, and public compliance.

The durability of this arrangement lies in its ideological adaptability. The system is not captured by one faction’s worldview; it is engineered to metabolise any ideological package that can serve as a delivery vector for control logic. Socialism, neoliberalism, environmentalism, identity politics, and behavioural management each enter the architecture as branded entry points, only to be stripped of their rhetorical distinctiveness once absorbed into the credential-gated enforcement loop. The result is a permanent managerial class—self-legitimating, transnational, and functionally immune to electoral disruption—that governs through the continuous updating of technical standards rather than through the visible contest of political programmes. Governance becomes hardware. Operators execute rule updates via credential audits, harmonised metrics, and enforced standards—each node self-replicating, insulated from democratic override.

Overlords Part 8 will dissect this managerial class directly—mapping its recruitment channels, credential ladders, and cross-sectoral loyalties—and show how the living operators, rather than the ideological banners, are the true carriers of systemic continuity.

Published via Journeys by the Styx.

Overlords: Mapping the operators of reality and rule.

—

Author’s Note

Produced using the Geopolitika analysis system—an integrated framework for structural interrogation, elite systems mapping, and narrative deconstruction.